By: Asal Taheri

In the quiet of night, when cities sleep, a solitary figure moves through the streets, armed with stencils and a vision. This is Banksy, the anonymous artist whose work has transformed urban walls into platforms for protest and reflection. For over two decades, his provocative art–sharp, witty, and unapologetic– has challenged authority, war, and consumerism, captivating audiences from Bristol to Gaza. His murals appear without warning, sparking global conversations, commanding millions at auction, and yet, he remains a shadow, unseen by cameras or police. Who is this elusive creator, and how does he wield such influence while guarding his identity? Step into the enigmatic world of Banksy, where art meets rebellion with a human pulse.

The Man in the Shadows: Banksy’s Identity

Banksy is a pseudonym for a British street artist, activist, and filmmaker, likely born around 1974 in Bristol, England. His true identity is a closely guarded secret, though speculations point to names like Robin Gunnigham, a Bristol native, or Robert Del Naja of Massive Attack. His art, defined by precise stencils and biting social commentary, speaks louder than any biography. Emerging from Bristol’s underground, Banksy uses rats, children, and soldiers to reflect society’s flaws, creating work that feels deeply personal yet universally resonant, as if he is painting our collective conscience.

From Bristol’s Walls to Worldwide Fame

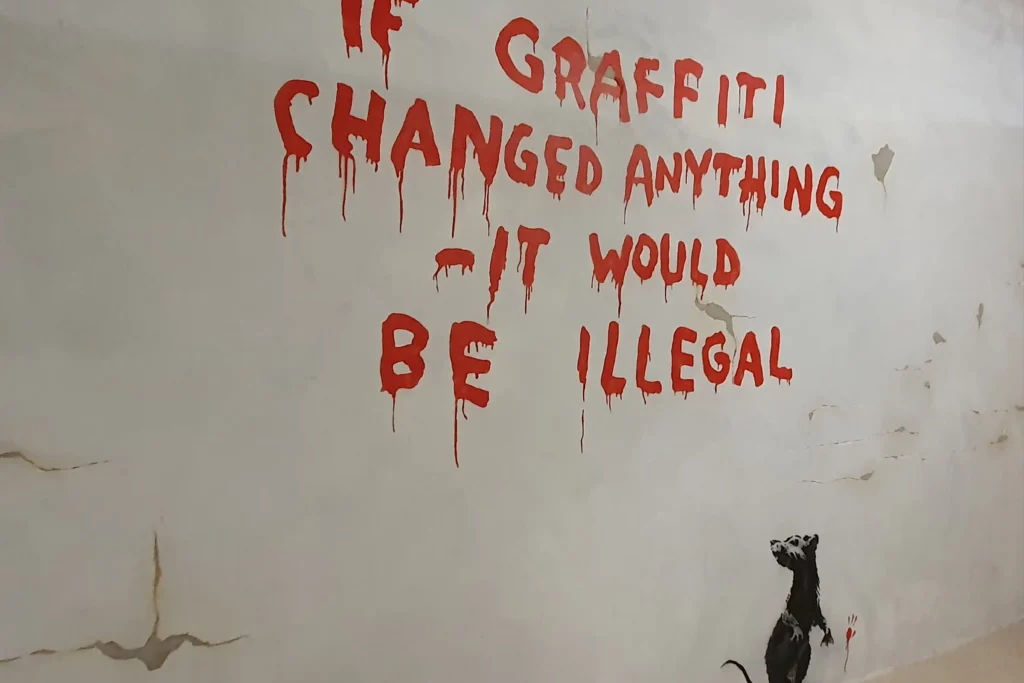

Banksy’s journey began in the early 1990s as a freehand graffiti artist with Bristol’s DryBreadZ Crew, influenced by local artist 3D and French stencil pioneer Blek le Rat. A near-arrest while hiding under a train in 1994 led him to stencils for their speed and precision. “I needed a way to paint and not get caught,” he recalled. His early Bristol murals—rats symbolizing rebellion, policemen in surreal poses—caught local eyes. By 2000, he relocated to London, targeting high-traffic areas like Shoreditch with works like The Mild Mild West, a teddy bear throwing a Molotov cocktail. His 2001 Rivington Street exhibition, an unsanctioned show in a tunnel, drew 500 visitors and media buzz. In 2003, he ventured abroad, painting anti-war pieces in Paris and Berlin, followed by New York in 2004 with stencils on Manhattan walls. His 2005 West Bank murals, including children digging through the barrier, marked his global pivot, amplified by viral online sharing.

The 2009 Banksy vs. Bristol Museum exhibition, with 300,000 visitors over 12 weeks, solidified his fame, showcasing 100 works alongside museum relics. This strategic expansion—from Bristol to international cities, leveraging media and the internet—turned Banksy into a global phenomenon.

Art as Provocation: Iconic Works and Controversies

Banksy’s career is defined by audacious acts. In 2004, he distributed fake £10

Notes at Notting Hill Carnival, replacing the Queen’s face with Princess Diana’s, causing a stir when some were spent. In 2005, he infiltrated museums like the MoMA and Tate Britain, hanging works like a soup can labeled “Tesco Value.” That year, his nine West Bank barrier murals, including a ladder to the sky, drew global attention to the Israel-Palestine conflict. His 2015 Dismaland in Weston-super-Mare, a satirical “theme park” with decaying castles, attracted 150,000 visitors in six weeks. In 2918, Girl with Balloon shredded itself at Sotheby’s after selling for £1.04 million, renamed Love is in the Bin. Critics label his work vandalism—Bristol’s council removed 12 murals between 2006 and 2010—while others argue his auction success betrays his anti-establishment roots. In 2007, he sparked debate by painting over a mural by street art pioneer Robbo, igniting a feud. Yet, his provocations keep us questioning power and privilege.

Madrid’s Banksy Spectacle

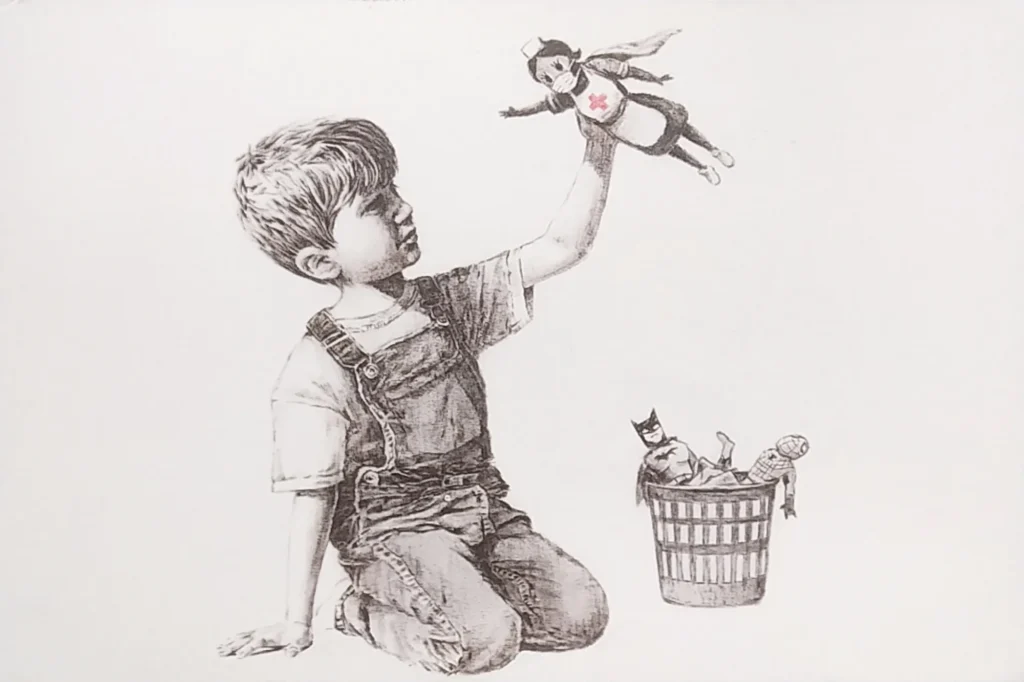

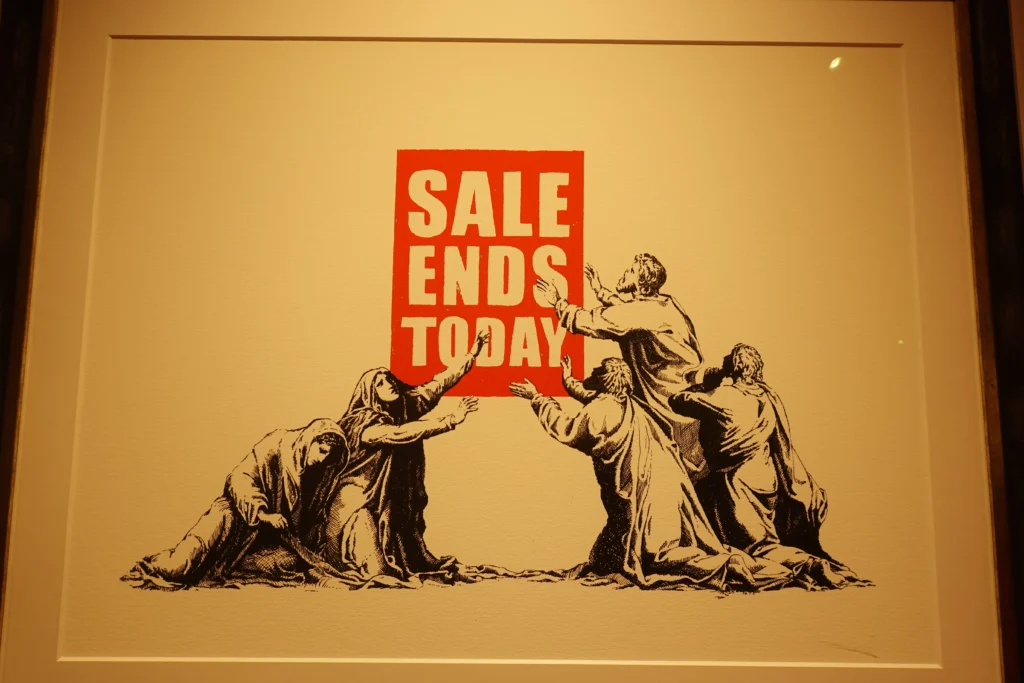

In October 2024, Madrid became a global hub for street art with the opening of the Banksy Museum at Paseo de la Esperanza, Arganzuela, a permanent exhibition showcasing the enigmatic artist’s universe. Housed in a revamped industrial space, formerly an old parking garage, the museum features over 170 pieces, including life-size reproductions of iconic murals like Rage, the Flower Thrower, and Girl with Balloon, alongside paintings, sculptures, and silkscreen prints. The immersive setup, with graffiti-mimicking walls and a free audio guide in English, Spanish, and Catalan, transports visitors into Banksy’s world, blending raw street aesthetics with curated storytelling.

By December 2024, the museum had drawn over 50,000 visitors, per Tripadvisor, with reviews praising its “revolutionary” vibe and comprehensive look at Banksy’s social critiques. Interesting facts include its collaboration with Steve Lazarides, Banksy’s former photographer, providing rare archival photos, and the inclusion of two large-scale originals, Pissing Guard and Out of Bed Rat, displayed for free in the lobby. Despite not being authorized by Banksy, the exhibition, open daily from 10:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Thursdays until 9:00 PM), has sparked debate for its high ticket prices, which some see as clashing with Banksy’s anti-capitalist ethos. “His work challenges you to think, and this space captures that,” said curator Alexander Nachkebiya, emphasizing its emotional impact.

Banksy Market: Art, Money, and Irony

Banksy’s anti-capitalist ethos clashes with his market dominance, fueling an estimated $50 million net worth. His piece, Game Changer, sold for £16.7 million in 2021, with the proceeds donated to NHS charities, while Devolved Parliament fetched £9.9 million in 2019. Since parting with agent Steve Lazarides in 2009, Banksy’s Pest Control office, not a traditional agent, authenticates and sells prints like Laugh Now, starting at £500 but reselling for £100,000+. He earns through limited-edition prints, books like “Wall and Piece,” and films like “Exit Through the Gift Shop,” which grossed $5 million.

Projects like Dismaland (attracting 150,000 visitors) and the 2019 Gross Domestic Product shop, which sold £850 stab-proof vests, blend critique with commerce. He refuses to sell street murals, yet collectors remove them—Slave Labour was cut from a London wall in 2012, sold for $1.1 million. Bristol gains £20 million yearly from Banksy tourism, per a 2019 study. Legal battles, like a 2020 EU trademark loss over Flower Thrower due to anonymity, highlight challenges, but charitable acts, like funding a £200,000 refugee boat, balance the irony of his wealth. “The art world is the biggest joke going,” he once wrote, skewering its elitism, but as his empire grows, one wonders: Is he mocking the market, or is the market mocking him?

The Art of Invisibility

Banksy’s anonymity is a logistical marvel. In some interviews before his global fame, he appeared with his face partially obscured, revealing little but fueling speculation. His pre-cut, portable stencils allow murals to be completed in under 10 minutes, as seen in works like Kissing Coppers (2004) in Brighton. “I’d be a lot less productive if I had to deal with fame,” he told The Guardian in 2003. Pest Control and a tight-knit team manage logistics, using encrypted emails and voice-altering technology during interviews to protect his identity. Murals are scouted in advance, often disguised as construction work, as with his 2013 New York residency.

Theories suggest Banksy is Robin Gunningham, supported by a 2016 Queen Mary University study linking his works to Gunningham’s movements, or a collective due to his global reach. In 2025, Banksy faces legal pressure from Full Colour Black, a greeting card company suing to strip his trademark over the word “Banksy,” which may require a representative to testify about 2017-2022 sales. A separate defamation lawsuit by Andrew Gallagher over a 2021 Instagram post adds further scrutiny, though no ruling yet demands he reveal his identity.

Banksy’s murals span continents: 31 works in 31 days during New York’s 2013 Better Out Than In residency, a 2015 kitten stencil on Gaza’s bombed ruins, and 2022 murals in Ukraine’s war zones. His Instagram, where he authenticates works post-creation, suggests centralized control, but site scouting and material transport likely involve collaborators. His consistent, sardonic style points to one creative mind, though a small crew likely aids execution. In 2018, he funded the Louise Michel refugee rescue boat, hinting at organizational depth. “Anonymity is his shield,” says gallerist John Brandler, amplifying his mystique.

Copycats and Kindred Spirits

Banksy’s influence has sparked a global wave of stencil artists, each adapting his creative style ot local struggles. In Brazil, Nunca blends Banksy’s social commentary with São Paulo’s pixação graffiti, painting indigenous figures to critique urban displacement. France’s C215, known for vibrant stenciled portraits in Paris, echoes Banksy’s humanism, focusing on refugees and the homeless. In the U.S., Shepard Fairey, creator of the Obama Hope poster, adopts Banksy’s bold aesthetics but leans into graphic design, though some criticize his commercial ventures as less subversive.

Egypt’s Keizer, active during the 2011 Arab Spring, stenciled tanks and doves, inspired by Banksy’s anti-war motifs, per Al-Monitor. Syria’s Abu Malik Al-Shami painted hope in Aleppo’s ruins, mirroring Banksy’s warzone interventions. Some copycats, like Mr. Brainwash from Banksy’s 2010 film, produce commercialized imitations, lacking depth. “Banksy showed us walls can speak louder than news,” Keizer said, capturing his global ripple effect. These artists, while distinct, carry Banksy’s torch, using public spaces to challenge power.

In Iran, Mirza Hamid, dubbed the “Banksy of Iran,” paints monochromatic figures with red earth pigment, evoking ancient cave art, on Tehran’s walls. His hundreds of murals, often painted over by authorities, critique societal issues subtly, inspired by figures like Darvish Khan Esfandiyarpour, who protested land reforms through symbolic stone gardens. Hamid’s work, featured at the Victoria and Albert Museum’s 2021 Epic Iran exhibition and New York’s NADA Foreland in 2022, gains global acclaim, yet he remains anonymous, per UPMAG. Also in Iran, Black Hand uses stencils to satirize issues like organ trade and women’s stadium bans, with a 2014 mural of a female football fan holding dishwashing liquid going viral, per The Guardian.

A Canvas for Tomorrow

As the world races into an uncertain future, Banksy’s uninvestigated presence looms larger than ever, a silent promise that art can still disrupt, provoke, and inspire. His stencils, whether on crumbling warzone walls or in polished galleries like Madrid’s showcase, remind us that creativity thrives in defiance of control. What lies ahead for this shadow artist? Will his anonymity hold against legal pressures, or will a new generation of stencil-wielding rebels—already echoing his style from Tehran to São Paulo—carry his torch? Perhaps Banksy’s greatest legacy is not in the millions his works fetch or the headlines they spark, but in the questions they leave unanswered. “Think outside the box, collapse the box, and take a sharp knife to it,” he once urged. In a world increasingly walled by conformity and surveillance, Banksy’s art dares us to imagine a future where walls don’t divide but unite, where every blank surface is a canvas for truth, and where the uninvestigated can still change everything.

Quotes:

- “Some people become cops because they want to make the world a better place. Some people become vandals because they want to make the world a better place.”

- “Graffiti art has a hard enough life as it is, before you add hedge-fund managers wanting to chop it out and hang it over the fireplace.”

- “People who enjoy waving flags don’t deserve to have one.”

- “The greatest crimes in the world are not committed by people breaking the rules but by people following the rules.”

additional Videos:

https://youtu.be/yYDno8W1f8s?si=9ifxNf0i-xl_STf7 (Banksy- interview on NPR All Things Considered, March 24, 2005)