BY: Trends Editorial Team

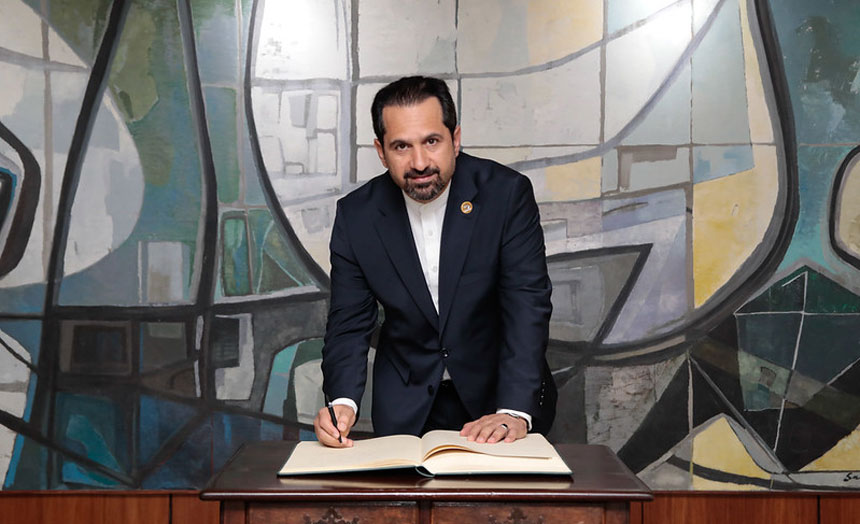

HE. Ambassador Hossein Gharibi

Iranian Ambassador to Brazil

Hossein Gharibi, born on February 14, 1969, has been the Iranian Ambassador to Brazil since March 2020. He earned his bachelor’s degree in Diplomatic Relations, and a master’s degree in Diplomacy in International Organizations from the School of International Relations, followed by a Ph.D. in International Relations from Allameh Tabataba’i University. Gharibi served as Deputy Director of the Center for Diplomatic Training in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1997 to 1999, when he assumed his position as Third Secretary at the Iranian Embassy in Rome, Italy, until 2003. He then served as an expert on foreign litigations in the Legal Claims Division of the International Legal Department in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, before being appointed head of the division in 2009. From 2005 to 2009, Gharibi was First Secretary in the Permanent Mission of Iran to the United Nations in New York, while also acting as an Expert on Development in involvement with United Nations Specialized Agencies. He was also a member of the UNICEF Executive Board for two separate terms of 2005 to 2009, and then 2012 to 2015. During his second term in New York, Gharibi held the position of political counselor and Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Coordinator of legal matters in the Permanent Mission of Iran to the United Nations. He was also Vice Chairman of the United Nations General Assembly Sixth Committee in 2014. From 2016 to 2018, Gharibi was an advisor to the Deputy Foreign Minister for Legal and International Affairs. Prior to his appointment as the Iranian Ambassador to Brazil in 2020, Gharibi served as Assistant to the Foreign Minister from January 2018 to March 2020.

Thank you so much for giving Trends this exclusive interview despite your busy schedule, we are very grateful.

How would you describe current economic, political, and cultural relations between Iran and Brazil, and what is your assessment of the affairs compared to other Latin American countries?

There are remarkable capacities in terms of political relations between the two countries. We face no challenges and enjoy close rapport, particularly with the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the other cabinet members. However, we have yet to reach our full potential with regards to high-level political ties. Potentials for the development of cultural exchange are unlimited despite the hiatus in cultural activities during the Covid-19 outbreak, which is gradually coming to an end. We organized an exhibition of handwoven carpets in Sau Paulo, a cartoon exhibition in the University of Brasília and we are preparing to hold another exhibition in a southern city. Initial research for two large cultural events is also underway. Trades saw a drop in 2020 before recovering the following year and are experiencing a boom this year. Our most important export is urea fertilizer, which reached a peak last year, while our main imports are soybeans, corn, and to a smaller proportion sugar and beef.

How have Iran-Brazil relations evolved through history?

Iran and Brazil have 120-year relations, mostly free from tension and issues, which is a solid framework for effective bilateral relations. Brazil was ruled by a military regime from the 60’s to the 80’s and Iran’s Islamic Revolution occurred in 1979. Yet, neither event disrupted the countries’ bilateral relations. However, when I first arrived in Brazil, the conditions were somehow different from what they used to be, but we managed to steer things in the right direction and emphasize mutual interests. We will soon celebrate the 120th year of our bilateral relations, which is a turning point in our partnership.

What are the challenges and issues in Iran and Brazil trade?

Sanctions are a major issue. Iran’s trade relations with Brazil have two main areas, one of which is largely hindered by sanctions. However, the other area including food and agricultural products such as corn, soybeans, sugar, oil, livestock inputs and press cake, which account for the largest proportion of our trade, have not been hit as hard. While such commodities are normally not subject to sanctions, sanction induced restrictions still apply under specific circumstances. To illustrate, products need to be transported after purchase is made, but sanctions that target the shipping industry limit humanitarian trade by curtailing the mobility of goods. Sanctions on the banking sector in general, can also influence specific food and animal feed deals.

|

|

This calls for effective policies for all circumstances. Distance is viewed as an obstacle, but its effects have in fact been mitigated to a large extent. Much human interaction is now performed virtually. Before implementing a project, the parties need to interact, exchange technical data, agree on the quality and price, and discuss details. People used to travel several times for meetings before finalizing a project. There were also fewer flights available and the farther the distance was, the harder it would be. Currently the largest portion of the arrangements are done online. The other barrier is the physical dimension and the transportation of cargo. Ports connected to international waters are set apart by water bodies that stretch thousands or tens of thousands of kilometers. However, once vessels are loaded, the duration of the journey, whether it is two or three weeks, is insignificant. I believe that any two ports with access to international waters are in fact, neighbors. For instance, a 60-thousandton cargo can be easily loaded here and unloaded in Bandar Abbas whereas transporting the same cargo to a nearby country without water access is extremely difficult. Therefore, we need to transform our view of geographical distances as the Chinese and Brazilians did. In 2000, these two countries’ trade totaled 3 billion dollars and has now reached over 120 billion dollars, which is a fortyfold increase.

Portugal and Brazil: Two Nations Bound by One Language

What kind of service and support does Iran’s embassy in Brazil offer Iranian enterprises, traders, and investors?

Bear in mind that embassies are not traders, businesses, or specialist agencies. Diplomatic missions are not authorized to start direct economic dealings with businesses. However, they have the following unique capacities. Firstly, the embassy has expert knowledge and a comprehensive understanding of the host country, which must be reported back to the home country. The embassy monitors political, economic, and cultural transformations, elections, and other events, and communicates them to corresponding agencies in the country.

The other advantage of diplomatic missions is access. No matter how large a business is, it cannot easily contact the president, minister of economic affairs, president of the central bank, senators, members of parliament and state governors. Embassies can provide the economic sector of their countries with this kind of access and use it to pursue the economic goals of the private sector and state-owned enterprises. It is worth noting that when the size of the public sector was disproportionately large, the private sector was mainly viewed as profit-seeking and undeserving of public and state support. This stance must be changed. The government and embassies need to realize that the interests of the public are intertwined with those of the private sector and avoid alienating it. We need to work towards our national development goals. Any foreign representative, including embassies and consulates, needs to prioritize national interests. There have been complaints from the private sector in that regard, which are at times legitimate. However, the services that we provide are regulated by guidelines stipulating that any activity must be reported back to avoid potential problems. The third capacity of foreign missions is their convening power.

200 Years of Brazilian Independence

Actors and stakeholders from the public and private sectors in the host, the home or even a third country may need to come together, discuss a project, and share ideas. But creating this level of collaboration is not possible for everyone. This is where only the embassy can convene due to the status of the ambassador. This convening power is believed to be one of the greatest services of the United Nations to the international community. As an internationally recognized organization, the United Nations provides a forum for countries to convene based on their commonalities. It can assemble regional groups of Member States, developing countries and Small Island States, the Non-Aligned Movement and Group of 77.

Embassies have similar powers. The ambassador could invite people from a Brazilian company, a Dubai-based shipping company and a financial firm in Singapore to a video call and they would not hesitate to join. This is done by virtue of the ambassador’s credibility as an official authority from the home country. The fourth role of foreign representatives is synergy. The embassy has authoritative power while the private sector, specialist services and banks have potentials of their own. Coordinating these sectors to form a unified body is the most important function of the embassy. Foreign missions can create projects by bringing parties together, following which they can monitor the development of projects.

Statistics suggest that trades between Iran and Brazil are one-sided and mainly directed towards Iran. Do the Foreign Ministry and the diplomatic mission have policies to create a balance in trade relations?

Though a powerful agent, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is only one of the many bodies functioning as foreign policy actors and influencing foreign trade policies. As Iran’s trade with Brazil is influenced by Iran’s multifaceted foreign trade policies, I believe that the general attitude needs to be reshaped. The issue was recently stressed by the President and the Foreign Minister, following which central agencies and representatives received guidelines demanding a focus on the promotion of economic diplomacy. I have seen foreign officials take the initiative in several meetings to even discuss hundred thousand-dollar economic deals. For example, they may mention a business in Iran, whose accounts have been blocked, and ask us to help solve the problem. Tangible and current issues are clearly at the top of the agenda. Even high-ranking figures attempt to use every opportunity to resolve challenges in trades.

It is essential to adopt this attitude. Officials are at times asked to discuss commercial affairs in meetings, like sales of agricultural products. They might object on the grounds that they should not be expected to address trivial matters, but business dealings are not insignificant. Trades and a strong economy are a source of national power, and everyone has a role to play in developing this power. Officials who take the initiative and engage in negotiations, even for small projects, may be able to tackle some issues and lay the groundwork for other businesses. Reaching a compromise with the other side can solve some commercial and economic issues.

Is there an action plan to ensure technology transfer in areas where Brazil has a competitive advantage such as agriculture, livestock production, energy, automotive industry, and biotechnology? If yes, what sort of cooperation are underway?

The Islamic Republic of Iran lies in a mainly arid region and will be facing more problems if we do not modify current agricultural structures. Our imports of agricultural products amount to 30 million tons, which is a significant figure and would leave the country with no water were we to cultivate this volume in the country. Brazil and the other Latin American regions enjoy an abundance of water and have relatively stable temperatures throughout the year, leading to remarkable agricultural capacities. Brazil has a population of 210 million people while it produces foodstuffs for 1.5 billion. The country harvests 135 tons of soybeans and 106 million tons of corn. With a livestock population of 215 million, it produces large amounts of dairy products. Brazil also produces great quantities of beef, most of which is exported, with Iran as a long-term export destination. Animal husbandry and cattle farming require large amounts of water, making food security in Iran and other countries in the region reliant on Brazil. We can have two possible approaches to this region. One would be to come here and shop for products and take them back. The second approach is to create sustainability of supply, which can be achieved reciprocally.

Using the economic complementarities of the two countries we can introduce attractive commodities that we are good at producing to the market, and in return import required products we cannot produce because of excessive water consumption. In many areas in Brazil there are three crops a year and soybeans, corn and cotton are cultivated with high proficiency, which is a rare advantage. Latin America, therefore, merits a long-term and strategic perspective along with all the other regions that we have ties with. Any country that we have relations with offers unique advantages, and Latin American countries are exceptionally important for us in terms of agriculture and food production and economic complementarity.

Considering the tourist attractions of the two countries, are there statistics available on tourist arrivals?

We have no exact data particularly because Brazilians can apply for visas on arrival at airports.

What is your personal experience in Brazil and your perception of Brazilian culture and people?

This was discussed in my meeting with President Bolsonaro. We agreed on clear commonalities and our ability to pursue mutual interests. I expressed my will to focus on these commonalities and use our trade opportunities while I’m in office. My friends and interlocutors in the Brazilian Congress, administration, and governors’ offices, who are good friends with the President, share this view. In our meetings we put emphasis on ways to go beyond agriculture and expand our relations to the mining, pharmaceutical, medical device, and transportation industries. We need to eliminate barriers and create opportunities as the economies of both countries have been hit by a common foe, Covid-19. Now we need to contain and respond to these losses through bilateral relations. In line with this attitude, I hope to succeed in making important changes, especially because the new administration is working diligently and intensively focusing on prioritizing economic development.

Are you optimistic about nuclear negotiations? How will they affect Iran-Brazil trade relation?

The ongoing nuclear talks are instrumental, in that they focus on lifting the oppressive sanctions against Iran and defending the rights of our nation. From a historical point of view, diplomacy and negotiation have long been prioritized in Iran’s approach to settling international issues and disputes. The point, however, is that interaction and expansion of foreign relations should not be procrastinated until the nuclear deal is made. The Supreme Leader recently provided strategic guidelines titled “neutralization of sanctions”, which will determine policymaking frameworks in foreign diplomacy.

Accordingly, nuclear talks to remove sanctions will be pursued alongside efforts to nullify them. A look at the history of the two countries’ trade partnership, even at the height of sanctions, demonstrates that the two countries can move forward with their foreign trade in the face of restrictive measures. Having said that, although Iran and Brazil’s have displayed apparent resolve to retain and boost relations, the removal of sanctions would bolster trade ties.