By: Farid Atighehchi

Some Iranian assets frozen due to sanctions, have been released as a result of the Vienna talks and are halfway to reach Iran. The war in Ukraine and its spill over the Iran nuclear deal negotiations, developments in Russia’s relations with Israel and Turkey, and disruptions in the global wheat supply have Iran’s foreign policy machine overwhelmingly engaged. However, it might be naïve to assume a sustainable détente is reachable between Iran and the United States without much fundamental compromise in either side’s foreign policy. The US is in no position to inflict any more pain than the existing but damaging sanctions, and Iran has no good reason to play anything other than hardball. Both sides remain adamant.

The result is a protracted process that will not have much short-term impact on the Iranian economy. Of course, as many analysts are asserting, the removal of sanctions will lead to improvements in the current levels of exports, imports, welfare and eventually the nominal GDP. Nevertheless, the ultimate state of the economy will boil down to domestic policies rather than external factors. The reason is that the Islamic Republic of Iran has never been much integrated in the global system and friction with the West has unequivocally isolated Iran from the Western economies in recent decades. And while different political camps proclaim their opponents dependent on the West or the East, on the ground, Iranian tradesmen and businesses are more pragmatic than ideological, and conduct trade with whomever furthers their interests .

So economic motives, along with alignment of their interests with the state policies, will guide how Iranian businesses operate domestically and across borders. And as much as the market would like to anticipate good news of a détente anytime soon, it cannot. The opportunities for cross border business with Iran abound. However, beyond the sanctions, it is limited by policies inside the country. To get a better grasp of current public debate and the essence of the economy, let us review the state of production in the country and the political confusion and chaos that surround it. This way we get to have a rudimentary view of where threats and opportunities might be for improved production, and the general state of exports or imports.

To see more related articles please click here

The Background

It was some time around 1977 that Iran hired Arthur D. Little to prepare a report to support its argument for the need for nuclear energy in Iran, and an increase in the price of oil to about 11 dollars a barrel. But the West, especially the US market, found this proposal very unappealing and downgraded ties with the Iranian government. In the aftermath of that move, the US lost the kind of close military intelligence cooperation it had with Iran, an example of which was the Project Dark Green aerial reconnaissance program run by the CIA and the Imperial Iranian Air Force against the USSR. But the narrative may be less about political values than the realities of the global-market suppliers and buyers. By 1980, a barrel of crude petroleum was 40 dollars. So, it is not far from reason to anticipate the US reneging on the JCPOA to have similar results for high costs in the West. Discounting debates about the merits and dangers of being a nuclear threshold state possessing the technology to quickly build nuclear weapons without actually having done so, the need for clean, alternative energy seems to have had

sufficient support in the realities of the Iranian market. For example, the steep increase in demand for electricity, rooted in the early 20th century rise in consumerism, forced the government to build the Karaj Dam by 1961 – a dam 180 meters high and 390 meters long, to the north of Tehran. Such realities will eventually get reflected in how Iranian foreign policy, trade and businesses operate. And such economic understanding on either side of the border is necessary to get to new international arrangements that work. Iran has long been on top of the list of mid-income countries and despite growing class divide and Iranian Rial devaluation, the country still boasts relatively high disposable income.

However, international business presence in the country is anemic, costly and unstable. These have made Iran a lucrative but elusive market. While Iran continues to stay connected to the global system in export of oil and imports of goods, it defies many of the conventions and values that contradict its own tenets. Western businesses try to enter a market fundamentally governed by relation-based norms. The Chinese and the Russians are well-versed in navigating this arena but have ups and downs in their own background foreign policy that many a time keep them at arm’s length from Iran’s domestic market.

Evidently, veteran businesspeople, with experiences in markets such as Iran, Turkey and India, understand this notion well. However, that does not necessarily determine their success in building necessary relationships and demonstrating the required acknowledgement of cultural peculiarities in a business environment such that exists in Iran. And even then, before such relationships work, the market should also be welcoming of the products, and domestic competition should leave room for new entry. The Iranian state has reasons for favoring a good level of protectionism given how it finds itself at odds with global powers. So, the question of market entry for international companies, and its methods for doing so, are much decided by how effectively the state and the private sector would promote local production.

Disintegration and Decentralization

The Supreme Leader of Iran recently gathered a number of the business tycoons in the country to emphasize “knowledgebase economy,” and employment and improvement of quality in production. Started more than a decade ago, the “knowledge-based economy” programme is supposedly intended to reward any company for going beyond assembly and into actual manufacturing production.

Discounting its history so far, from editorials in Kayhan to critiques in other publications close to the state, advocate

s are giving new meaning to the phrase. There are few perceptions of interest in their interpretation –and cues to the policies to come. They include, for one, a focus on upgrading technology but to a bare minimum. Another is a wishful departure from the neoclassical notion of allowing growth to expand production of goods and services, vaguely but incorrectly resembling Marxist models of “exponential growth.” But at the end, these proponents of hardline economies are aiming for cost savings, mostly through maintaining aging machinery and replacing primitive practices of production. They argue that joining the global value chains is not possible due to sanctions and other forms of outside threats and competition. A recent parliamentary plan proposes a list of technological priorities to complete domestic value chains, especially in steel and food sectors, but also in livestock vaccines, pesticides, fertilizers, exploration and excavation machineries for lithium and silica, components for ECU in the automotive, turbine and extruders in the OGP, anti-explosion engines and automation systems in OGP downstream.

Despite such a wish-list, the overall political agenda is evidently far from innovation and specialization in a few fields, but rather a marginal progress in a wider array of industries and products. Another group, from among establishment’s top businessmen, claim to target the same goal but get there through fragmentation. Last year, the head of the Iran Chamber of Commerce expressed concern about the continued disintegration of manufacturing plants in saturated markets and urged his peers to break up their operations into smaller and more manageable enterprises. However, the possibilities for such split-ups are limited. Without getting too technical, suffice it to say that a majority of industries in Iran and their markets are not at a point to be segmented into separate units because of poor technology and standardization. It is interesting to note that the parliament seeks to prohibit government spending in select products and technologies seeking compliance with international standards.

The government policies and regulations are less about setting the course than implementing the top-level strategies pronounced by the Supreme Leader. Even then, the current cabinet members are visibly vacillating in their planning. The probable outcome of these inclinations, the subsequent policies they promise, and confusions in the administration for implementing them, is that larger players may try to break down less profitable activities and leave it to small and medium enterprises (SME) while the government pushes for technological upgrade among SMEs. However, as this is not an organic evolution of the industry, we could expect the result not being scintillating further inefficiency in production and pricing, supply disruption, inferior quality and rising prices of products. It is possible that the state will not force but instead encourage industries towards disintegration – especially in the agriculture sector with the concern for food security.

In the foreground of this outlook empty of consensus among top policy makers, is an unofficial misunderstanding between central and local authorities that could lead to unreasonable expectations and eventually disrupt the current modes of production at the micro level. Production and Fighting Over Competitive Positions The situation seems to open the possibility of higher returns for spending on taking over competitive positions. That would distract production from specialization and development of in-house competitive advantages because it makes more sense for enterprises to focus on trying to go after each other’s work, market share in imports, technological knowhow or, simply, the assets themselves.

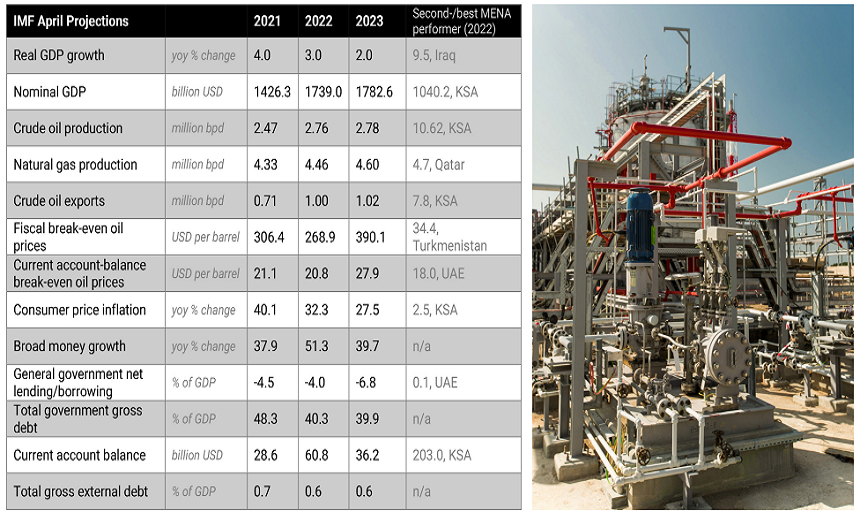

As this infighting is less in advertisement and product development, safeguards against hostile moves remain more expensive than the offense itself. This can hamper domestic technology development while imports remain limited to basic technological licences. Subsequently, any growth in production will be costlier than any gains from improving efficiency and it will reflect on the GDP over the next few fiscal years. In April, IMF projected the real GDP growth of Iran to decrease from 4.0 in 2021 to 2.0 in 2023.

The Local and the International

The growing incremental changes expected to come in the power structure could lead to more infighting and heightened competition over resources during a time of disarray. At the top, the notion of reintroducing the position of a Prime Minister or a parliamentary oversight system is gaining momentum. As a prelude, the program of “spatial planning” which brings together policies for development and use of land with other local policies and programs, is already incorporated in this year’s budget. Beyond a very generic quota plan in the center, resource allocation is set to be decided at the local level.

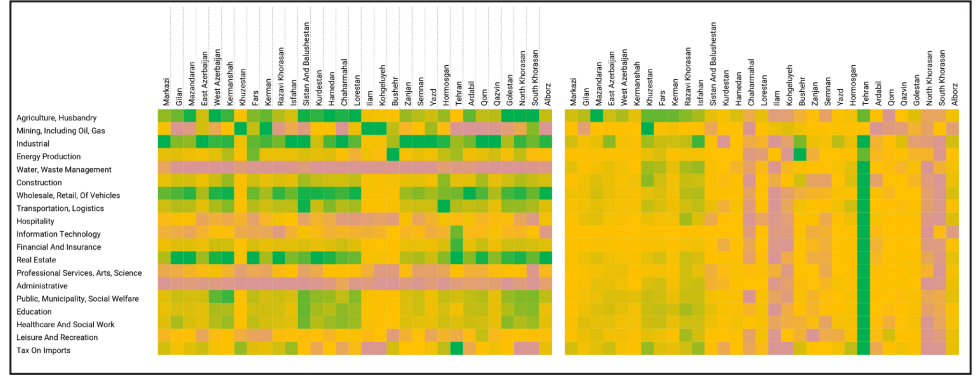

That initiative does not necessarily translate to competition between provinces because despite the perseverance and recognition of diversity of ethnicities across the country, some of the top tiers of local powers are fundamentally representatives of the central government in Tehran and are independent of local executive branches. This further causes friction over resources for production and could hinder variance of production from province to province. One question that is raised is whether this overall rebalancing of decision-making paradigm is in favor of a more competitive production, or does it simply decentralize the executive branch while keeping the state at an advantage over the private sector?

The answer partially points to supra-government economic powerhouses such as IRGC and unwavering monopolies held by such institutions and their affiliate individuals. Smaller, rather independent businesses would try and involve such entities directly in their ownership to protect themselves from possible unpredictable political changes as the “spatial planning” initiative. Amid this chaos, the matter of productivity and efficiency has little room to take center stage. Chances would be higher for innovation and growth where the market is more fragmented and has relatively low cash-flow problems. For example, some previous studies identified correlations between the sanctions against Iran and efficiency improvement and in one such study, unsurprisingly, that correlation was most strongly present in the well-distributed industry of nonmetallic mineral production.

Despite the vast array of ethnic concentrations across the country, competition among state players at local and central levels would undermine any bottom-up economic development and specialization that should guide any “spatial planning”. There is much potential for setting up shop in geographically different areas other than Tehran. This idea is not lost on the conservatives and state-affiliated individuals. In a recent interview, one such businessman discussed with me their plans for a new manufacturing venture in their hometown with “a priority over profit for creating jobs,” in line with the Supreme Leader’s announced criteria. However, Tehran dominates the country in terms of GDP by making up about 28% of Iran’s total added value –and even up to 83% in some consumer and production sectors.