By: Farid Atighehchi

There is no doubt that the outcome of the ongoing JCPOA negotiations could have a life-changing impact on Iran’s business community and its population; meanwhile there are many other factors affecting Iranians on a daily basis.

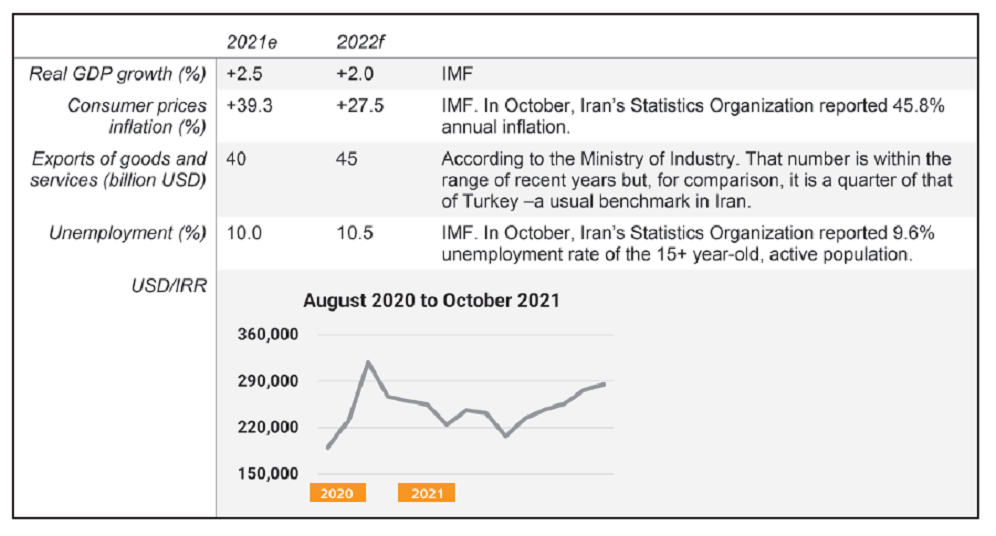

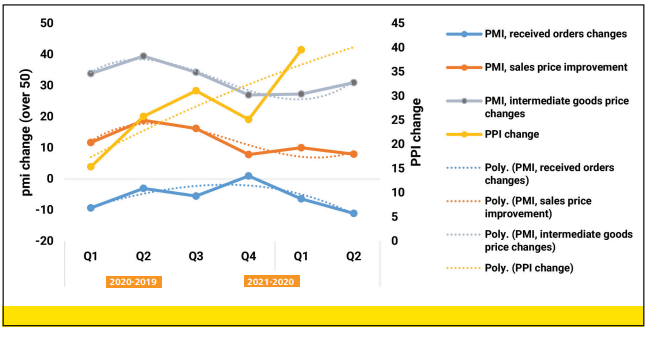

An unedifying inflation has put a weight on life and business short of choking .while years of unscrupulous environmental disregard is catching up with us, manifested in droughts and irrevocable destruction of an increasing number of ecological landscapes. Higher prices for intermediate goods are negatively affecting supply, and demand is already weakened by pandemics and just bad days. The inflation is much less the government’s doing than that of economic sieges and fearful allies. The government and the public both struggle with it but what the new administration plans to do in the name of its control may not only determine the trajectory of prices and purchasing power but also change the political complexion of the country.

More than 100 days into office, it is still not easy to tell straightforwardly what the policies of the new administration are. It may be benevolent that it has not rocked the regulatory scene with radical rules. Or it may be a sign of indecision. Or simply of too much caution. But there is one pattern seemingly emerging in the background and that is the public space inching further towards the private. Here we take a brief look at a few clues. But first, a short overview of the actual conundrum the government faces with its monetary policies.

There are too many variables at work. For example, on paper, if the government lowers interest rates, the banks could go on and not to hurry to get their funds back, and the money can go in capital-intensive investments. But if it does, then that exactly exacerbates inflation. So, the government will be more selective about who gets lower rates and when, and will otherwise keep the rates high for the rest of the market participants. There is severe rationing of resources and a large number of people who seek those resources. This means a selection process is unavoidable. The government must choose. It could and will, of course, use open market operations, started in the previous administration, to sell securities to draw out excess cash. However, that is a corrective measure only meant to adjust policies such as those for short-term interest rates.

The government also must avoid a terrible trap in its taxation and subsidies. With the current and prospective budget deficits, the government inevitably has to experiment with its taxing agenda. And here it might just go after the easier catch: After more than a year and many exemptions to the idea of taxing unoccupied residential real estate assets, that law is not enforced even in its current weakened form. At the same time, the parliament and the government have enacted, regulated and issued memos in a matter of weeks to tax “social media celebrities.” As for taxing of income and other sources of earnings, a large number of the population is already under the poverty line and many are teetering on the precipice according to the government. Meanwhile, the new administration may be reluctant to tax the big fish outside a friendly case-by-case setting. What it is doing, instead, is accelerating the groundwork to import vehicles, historically government’s second source of revenue. Whatever happens, the government is cooking up new taxing plans that may be ad hoc or more fundamental. The waiting is disconcerting. According to officials, there is an estimated $60 billion a year in subsidies that are unjustifiable.

The majority of subsidies in Iran go to fuels of all types, residential natural gas and imports. Some voices in business circles are suggesting that if the government wants to reduce these subsidies it should target imports. Subsidies in imports are in the form of dual exchange rates. The gap between few subsidized exchange rates and that of the free market is huge, and whoever has access to such rates enjoys an immense advantage. Dual exchange rate systems are basically transitory. They are not supposed to be there for long periods of time. They are set up by governments to move from one exchange rate regime to another one.

In Iran though, it is part of the landscape. That estimated $60 billion of subsidies would be a whopping 30% of the country’s GDP. That means $60 billion that could be spent on development projects. At the same time, although subsidies for the essential goods are strategic and welcome, their distortionary effect is otherwise the opposite of public development agendas. But here again the government is in a conundrum. Removing subsidies that directly help or eventually find their way to consumers will put further pressure on demand and in turn on businesses. Going around that would be loosening money supply which then rises inflation.

Saeed Mohammad, head of Iran Free Zones, recently visited Kish Island, where he announced he plans to set up offshore banks, unlinked from the Central Bank, to operate in free zones. This will be accompanied by exchanges that offer securities. He went on stress these are especially to facilitate the 25-year agreement with China.

There are other reasons as well not to expect the dual exchange rate to go away. One reason for having them is to insulate the economy from shocks in the global system. Although statistics indicate subsidies for imports is only around $7 billion, if the price and supply of strategic goods were to be disrupted that would create major problems. Iran has a small economy and more than a fair share of tensions with neighbors, regional players and superpowers. If that $7 billion is not insulated, international capital movements that are relatively small for many of Iran’s foreign rivals would pose risks to the industrial supply chains and the national social welfare. What happens with the dual system then depends on a consensus in the state about its perception of vulnerability of the economy to external shocks and its expectations of financial moves against it from the outside. But it is not just some billions of subsidies that make trouble. It is the frenzy of free market exchange rate movements as well. Not only Rial devaluation threatens the value of economic output but its volatility deters investors from putting in capital.

Favoritism as Necessity:

In the meanwhile, there is a dearth of issues with economic policies to redistribute resources and production domestically. It seems that the pace of rising intermediate goods prices is more than that of sales. Subsequently, net economic output has slowed down and the Central Bank is finding itself in a position where it has to put a break on the growth of money supply or see the inflation shoot up. But tightening the money supply will drive capital further away from the industries and lead to further economic slowdown. A real pickle.

The government then needs to make choices as to who will receive investments and how; a kind of political targeting is inevitable. The administration is talking about new mechanisms to go around this dilemma and alternatively “not to use money” for its investments, which implies some sort of a barter mechanism. It is also talking about choosing projects based on economic merit and value, but both these approaches have their limitations. Economic feasibility and efficiency have not been, historically, Iranian governments’ forte. There is no reason that would change over-night. There is also so much you can barter with. On both sides. It begs the question as to how much illiquid assets businesses are willing to take as payment and what assets or privileges the government is actually going to barter with. And all this is before the easier political criteria kick in.

On a side note, one of the assets that the parliament is publicly proposing for barter is crude oil. Last few years have been a feast for private dealers in oil, and their number and wealth has flourished. An ancillary outcome here will be a larger grey market of Iranian oil.

What could dramatically change all this is exports which the government claims is on top of its agenda. Rightly so. It is demanding that all of its branches come up with specific plans to facilitate exports. That is a long shot. Assuming public offices are competent and up to the task, private businesses, mostly SMEs, and the semi-private businesses, which make up most of the economy, are either already exporting or they are not good at it. It has not been a lack of statements and expressions of intentions from the government that held back others. But maybe the other route the government is taking will help. It says it wants to ensure that the government is not the problem. That is promising but we need to wait and see how they go about it.

Iranian governments have a long track record of inaugurating economically-, at times strategically-, infeasible projects. The new administration claims it wants to do differently. That would be out of necessity, and not as a political choice. Here, however, the close alignment between the parliament and the government might really help. Without conflicts of interest, with personal agendas resolved otherwise, the government may actually be able to be more careful with its spending.

What the government may do is to redistribute decision making that has traditionally been about lobbying a whole governing body, and instead to delegate it to regional centers. For this to happen it would first take a central role in deciding allocations for each region or province and then let the negotiations happen geographically. This would be a radical change and a difficult one to adopt but there are signals that the government will try and evolve on this path. Among these signals is the resurgence of the notion of “spatial planning.” For many years floating around, it may actually come handy this time and be put to use, one way or another.

Public-Private Partnerships:

In 2017 the government introduced a bill to facilitate public- private partnerships (PPP). The bill proposed that government could use its sources to pay for feasibility studies and then involve whoever is up to the task to engage in a number of schemes such as BOT, BOLT, TOT and buy back. The bill never took off.

For one, that bill suggested new contract designs and, in what we may call progressive given where regulation of legal services is headed, arbitration was proposed in a setting jointly accommodating public and private interests. But what actually killed the bill was circumventing the auctioning process to pick the private party. The bill wanted to use private or other third-party companies in credit rating and due diligence to help rate the submissions. That would mean that decision making process would be more transparent and had to be based on assessment outside the dark rooms of government offices. Naturally a large population of semi- governmental businesses rushed to excoriate the bill. It was denounced for how much it would lead to corruption. That is, until this very summer.

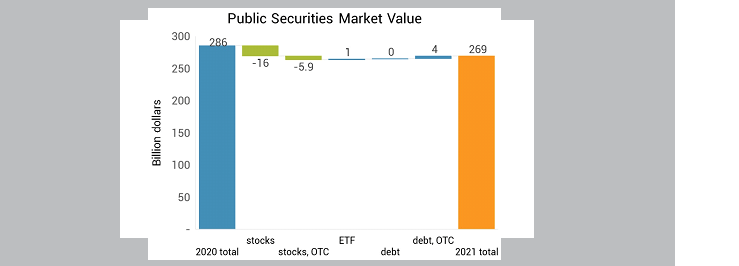

Figure 2 Changes in Tehran Stock Exchange reveal an exodus of mostly one- time, retail investors. They now put their money in gold, foreign exchange and recently in cryptocurrencies. Data from TSE.

Now advertised as a way for the government to relieve its central place in governance, public-private-partnership is finding the spotlight, again. And in a cruel twist, suddenly all the problems have disappeared. MPs are talking about how appropriate that bill is, but they have proceeded to introduce their own plans which propose almost exactly all the issues that were at fault the first time around, including using the project as collateral and the permission for the government to guarantee purchases.

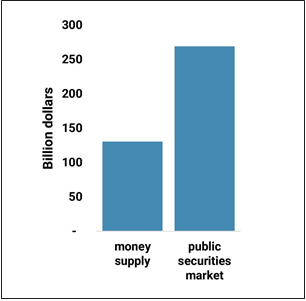

Figure 3 No one is holding cash. Even though TSE is not the only destination of investments, it is still much larger than the money supply. Data from TSE and CBI

In the proposed plan the state is asserting itself as the priority creditor. This means projects and other credit schemes are expected to pay out to the government until its target interest rate is covered before private stakeholders can take their share. But this is not common practice. Therefore, we could expect that the complexities that most of the economy cannot effectively handle, will lead to undermining such practices, further impairing realized returns the government counts on to receive. The plan gives new incentives but of course omits the controversial issues. It does one better apparently. It seems to pave the way for public servants to hold executive positions at both their office and the project, which otherwise would be against previous legislature. Consequently, the government may be further embedded in the economic activities of the semi-private businesses. This may help international trade and foreign direct investment to be further shielded from possible sanctions while government furthers its leverage in directing the market.

Retail and Private Investments:

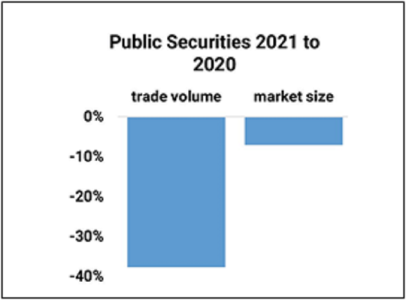

The previous government had its experiment with drawing quick money from the capital markets. We can see how trade volume has plummeted while the total size of the market does not reflect that decrease. The difference comes from the asset revaluation scheme that is just started slowing down recently, while first-time retail investors dropped out of the overblown market.

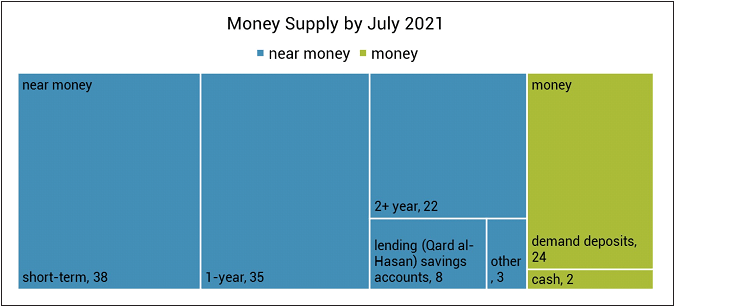

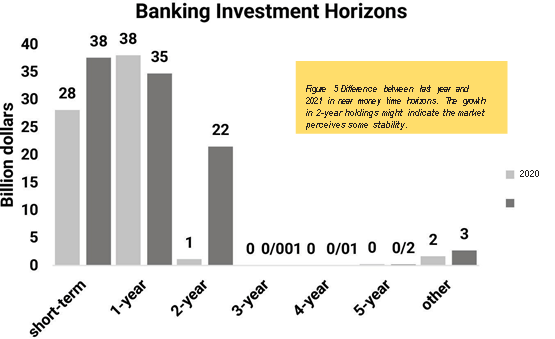

The weighted average price-to-earnings ratio in Iran skyrocketed throughout last year scoring 20.7 in November 2020 compared to 6.5 the previous year and 8.8 this year. Similar phenomena can be seen in other markets. For example, real estate prices jumped while the actual operating income from such assets barely caught up, driving real estate owners to sell or, either way, eschew from renting out. At the moment the money supply is dwarfed by the size of the public securities market. It is interesting to note that holdings are mostly short-term and most of the money is in one-year and short-term investments.

Figure 4 mix of money supply based on type. Values in billion dollars Data from CBI.

A recent, noticeable increase in the 2-year investments indicates a lowered market uncertainty but investments beyond two years are scarcely visited. Most of the wealth of Iranians is now in gold, foreign currencies, durable goods, even cryptocurrencies and most importantly real estate. The government will have a hard time convincing people to bring their capital to real economic activities –where they have to race against inflation, uncertain taxes and new requirements demanded by the government. This situation has no easy fix and, as a result, businesses will continue to experience cash-flow problems. Last year alone about 61% of all banking credits went into working cash flows.

Looking Ahead:

The new investment environment feels like the beginning of a new era where the terms of trade and manufacturing are no longer just negotiated at arm’s length between the government and the private and semi-private businesses. The government wants to bring leverage to projects, which

combined with expected lowered credit lines, means a necessary favoritism. There is too much fear of the outside world for the state to let the market go free but it also needs the private capital to be put to work.

In this context, one way or another, private and public interests may be further intertwined. This may be more than a short-lived situation. How exactly that will pan out we have to wait and see. For 2022, however, the measures seem congruent with the economic situation and dominant governance values. So, it is unlikely that inflation will go off the rails but the fate of the individual business remains uncertain.

Ghorbanzadeh, head of Privatization Organization, says candidate companies will be privatized incrementally, in block trades and under more strict conditions.