The Iranian economy witnessed a major disruption when the presidential helicopter crashed in May, resulting in the death of the President of Iran. What came next has been of even more of a surprise; the election of the moderate Dr. Pezeshkian as the President. The presidency holds a considerable operational power and the new government would seem a departure from the trajectory. The first cue, of how big a departure this is, is seen in the coalition cabinet. But it is more a question of quality of how this came to be and what it means for the economic future and statecraft of the state. Here we review the trajectory before the passing of President Raisi, how it all changed after his sudden replacement and what the new trajectory will look like.

The Trajectory

The trend of growth of Iran’s gross domestic product, GDP, a major indicator of economic activity of a country, has sunk downwards since 2012, when the Obama administration enforced its harshest sanctions regime against Iran since 1979. By 2022, the GDP was about half its peak, which coincidentally was in 2012. One would say, putting aside arguments about war and peace, that the west felt threatened by a rising economic power in the middle east that was not aligned with it. Iran, in response, hardened its position and adopted its “Look to the East” foreign policy where it would instead focus all its resources on improving trade relationships with the global south. As the west cut off the supply chains of Iran to the global north, to its allies in the South, such as Pakistan and India, and even forced China and Russia to some level of compliance, Iran instead went for self-sufficiency by supporting its businesses financially and upgrading production. However, that cutting off of ties was surgically precise and selective.

All was in tumult. A wayward public, angered by drastic rise in living expenses and lack of social freedoms, and an economy sinking into atrophy due to incompetence, lack of financing, lack of technology and even lack of skilled human resources plagued the Iranian response. Mass migration of Iranian financial and human capital alone has been of dire consequence and economy sustained numerous shocks. This was eventually about to change during the presidency of Mr Raisi.

In December 2023, Raisi signed into law the reform of the banking system. The law reconstructed the governing board of the Central Bank, CBI, and revised the authorities it could exercise. CBI set up the “centre for exchange of currency and gold” to implement its policy of converging different currency exchange rates in the market to within 8 percentage points of its discovered price. The centre even promised to introduce swaps, futures and option contracts for risk hedging in both currency and gold. Currently it processes bank notes and payment orders as the main channels of price discovery. Other administrations tried different interventions to contain devaluations of rial but it was Raisi’s administration that had enough political will and clout to implement a workable, sustainable and much less faulty mechanism than its predecessors’. This has been a full reversal in how foreign currencies work in

Iran. As the public relations of the CBI put it at the time: “CBI [now] buys the foreign currency from the government at 28,200 and sells it at the [fixed rate of] 28,500 to importers [of essential goods.] CBI used to buy foreign currency from the [exporters in the] market and allocate that at a lower price to the imports [of essential goods.]” On one hand, CBI no longer needs to print new money to inadvertently contribute to inflation. On the other hand, foreign currency is otherwise priced by discovery. However, angry voices began to rise, including in the parliament, where MPs lobbying for interest groups, clashed with both CBI and the government.

The principles regulating the banking sector was not updated since 1973 and it had failed the economy since the establishment of the Islamic Republic. But there was a price. The government was getting in the way of a portion of the economy whose interests it was undermining. This confrontation was publicly visible when the government, to ensure its new system would not get sabotaged, had the Bureau de change Association, the coalition of exchange traders, dismantled.

In early May 2024, Raisi signed into law the “Financing of Production and Infrastructure.” For the first time in the history of the Islamic Republic, a comprehensive set of financial support measures was introduced that included factoring, or selling accounts receivables, guarantee funds that anyone would be allowed to set up, swap contracts and a temporary device called “Anonymous Investment Package” that would disallow different state authorities to withhold or recall permits or otherwise hinder investment activities.

The Fall

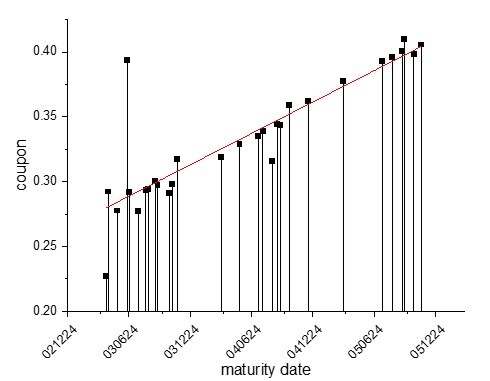

By May 2024 the yield curve, a measure of the health of investment activities, was normal for the first time in years. (See the figure) The economy was still in bad shape, though. This was conspicuous in the near-bankruptcy of the pension funds of Iran. Disgruntled voices against the policies also kept rising. The Iran Chamber of Commerce was one. It raised issue with removing its representation in the governing body of the CBI, coercion of black-market exchange trusts and measures that, as a report from the Chamber discussed in November 2023, “punitive regulations cannot produce economic order.”

Figure 1: The yield curve. Own study. Data from TSE.

The real threat to the government came from misaligned powerhouses, discontent with foreign exchange market regulation and CBI’s push for tighter rent distribution at banks. This started with lobbyist MPs derailing the new approach by inducing an imbalance in the government budget and its social security obligations by twitching the base rates for LNG and other OGP exports. This wreaked havoc on pension funds –though arguably they were already in a feeble state. Later, the head of the Mellat Bank, one of the largest banks in Iran, was pronounced dead by gas asphyxiation after allegedly using the new found powers, given by that law, to chase after a specific group for their default on debts –debts that are normally understood as rents and are not to be serviced. There was also a sudden number of changes at board levels of banks and their subsidiary financial institutions that took many by surprise.

Large rentier interest groups, who own both upstream industries and also imports of essential goods, shown the most discontent. A recent report from the Iran Chamber of Commerce called the government’s financial, foreign exchange, monetary and energy policies respectively recessionary, recessionary, inflationary-recessionary and inflationary. Even the growing trade deficit were widely publicised in the news and debates against the government. The problem is trade deficit, in its crude form, is barely a good econometric measure to discuss trade policies.

The “look to the East” would indeed fall short in the mid-term to revive the GDP to its record performance. We modelled this in an earlier essay that it would only raise, ignoring any exponential effects, the non-crude oil exports to the range of 75 billion dollars which is still 25% lower than the benchmark. However, it has a chance of working if the government could afford the high costs of misalignment and upgrade its production and linkages to, say, BRICS.

But in the afternoon of May 19, the helicopter carrying the President Raisi and the Foreign Minister Hossein AmirAbdollahian, along with several other dignitaries, crashed in the mountainous wilderness of north west of Iran. All passengers perished.

The Point of Inflection

In mid-August, soon after the coalition cabinet was introduced, the Supreme Leader gave a speech in which he admired the courage of martyred Raisi against enemies in the economic theatre, warned of divine wrath in case of “non-tactical retreat,” and emphasised the significance of the cultural arena. Media close to the conservative parts of the IRGC likened Raisi to Amir Kabir, a historical figure who promoted the national resilience and standing against foreign powers. Today, the foreign powers are no longer just the states but also companies in the global supply chains.

It was not long before the coalition government got approved by the parliament in its entirety. A first in more than two decades. The coalition is made up of politicians of pragmatic records. Most of them are visibly technocrats and their political affiliations obscured. Although, the career of many of them could be traced to Rouhani, Rafsanjani or rising stars such as Ghalibaf.

Figure 2: Vladimir Putin held a meeting with Speaker of the Islamic Consultative Assembly of Iran Mohammad

Bagher Ghalibaf on the sidelines of the 10th BRICS Parliamentary Forum in St Petersburg. (Source: Kremlin)

In the cabinet, a strong duality stands out between the Minister of Industry, Mohammad Atabak, and that of the Economy, Abdolreza Hemmati. These are the two ministries with arguably the most direct and significant impact on the economy and the business environment. Atabak is a former economic deputy in the powerful Bonyad Mostazafan. His tenure was during Parviz Fattah and he left the post along with him. Hemmati, on the other hand, has been the head of the CBI during Rouhani and the head of the Sina Bank, a subsidiary of Bonyad Mostazafan, during Saidikia. These are people who represent powerful but rival forces which have different views about the economy and specifically about linkages to global supply chains. Hemmati would advocate policies that favour linking to these value chains, including and especially in the global north. Atabak would advocate for policies that are protectionist, focusing on upgrading domestic production and supporting local businesses of low-value activities which better align with the Look to the East foreign policy. In return, this policy is a doctrine that the new Foreign Minister, Abbas Araghchi, another pragmatist conservative with career ties to both Jalili but especially Rouhani, would have to advocate. Among the issues and solutions Hemmati has announced to work on, a handful seem to be of real intent: interventions into the Tehran Stock Exchange, TSE, and reforming the banking system in dealing with foreign exchange. Hemmati, in the brief time he had to present his plans, specifically stated he would “lower” the currency exchange rates.

This is telling because the exchange rate would fundamentally only go up, whatever the change in trade levels. Raisi administration’s reforms of the banking system is arguably the most and maybe the only successful work on managing Rial devaluation. Given Hemmati’s track record in the CBI, this would be not about revamping for an improved system but rather a narrative that masks, at this point undeclared, interventions in the cross-border capital flows. Also, Hemmati’s points about the TSE is about the exchange’s pivotal role in financing. Again, there is not much that can be done in TSE from the top-down. For example, the entire market capitalisation of the TSE is smaller than the annual investment in real estate development. And it is not that the TSE has been failing the market because it has been slow to catch up; TSE has shown to respond to how financial institutes in Iran move to introduce new instruments. It is just that the market has been slow to demand new regulations and advancements. This is to say Hemmati plans to undermine the other achievement of the fallen government of Raisi in introducing the “financing law,” and move the focus away from those measures. Atabak’s plans on the other hand, again in the mere keywords he has had time to communicate, explicitly advocate for the promotion of domestic production and its financial support. This would naturally benefit businesses of low-value activities against those connected to global supply chains headquartered in the north. This is a continuation of Raisi administration’s policies. The coalition government then will be the space of negotiation where these approaches crash into each other. The only constant here is that, unless the coalition fails for consensus, the government will need to either lower interest rates or inject cash into the market in the very short term. During the Raisi’s, the latter was more probable and it is even more so now. The recession in the real estate segment alone, one of the worst since 2015, shows the urgency as real estate is a major factor in Iranian, and Tehran’s, GDP.

The New Trajectory

Two of the major accomplishments during Raisi, restructuring of the banking system and the financing law are here to stay. That is even if the extent they are actually enforced may become a matter of negotiation inside the coalition government and different forces may try to impose their own interpretation –as evident in the duality between the coalition’s Industry and Economy ministries in their desire to join or disjoin from the global supply chains of the north.

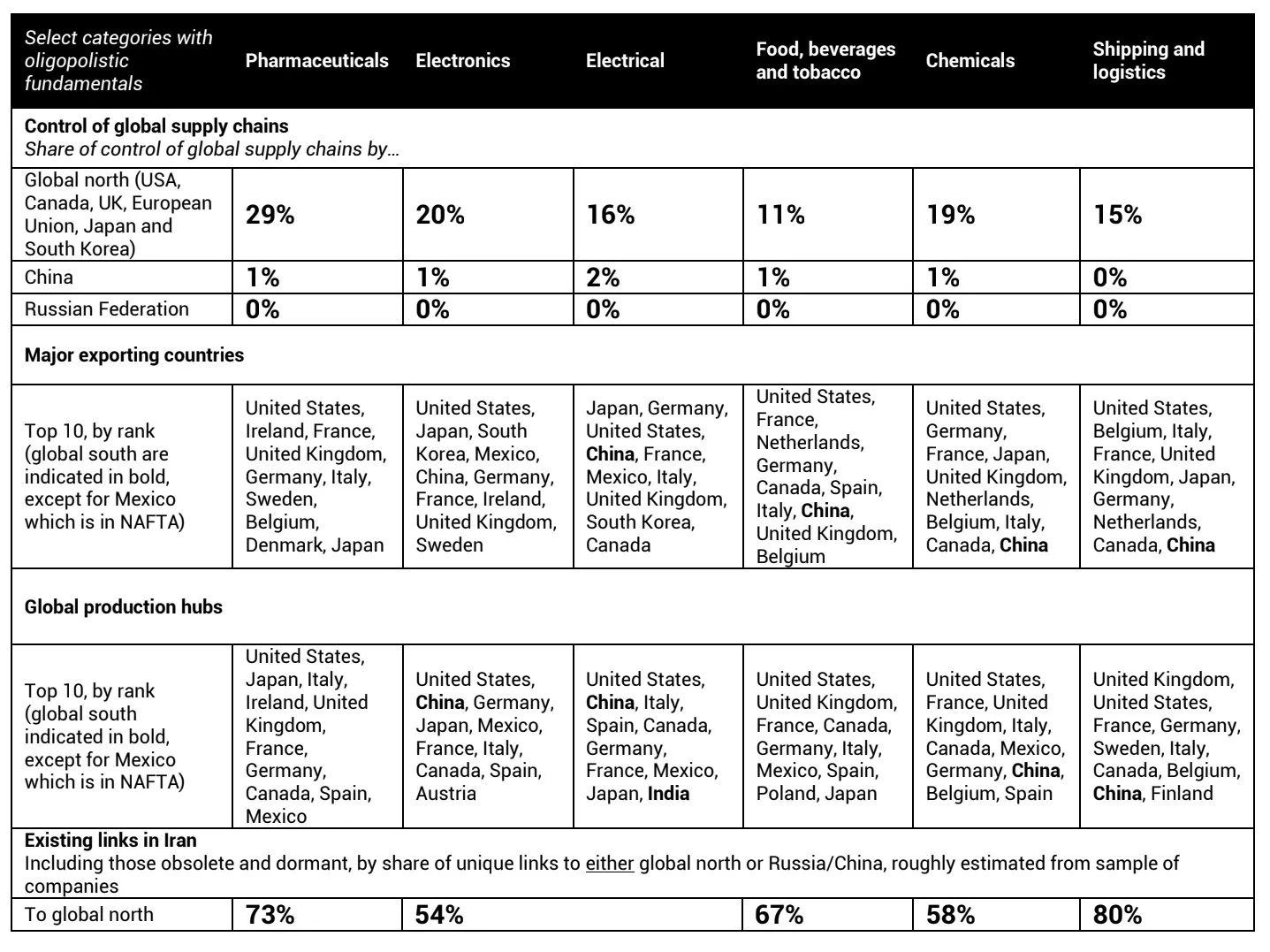

However, the problem of the look to the east policy and its costs are vicious and go beyond its failure, in the short term, to recover the economy; This is the space where states and their businesses either collaborate or collide. President Pezeshkian has argued that the state needs about USD200 billion in investments of which domestic sources can produce half and the other USD100 billion should be secured from foreign sources or otherwise, implicitly, international trade. In his outlining of his plans, the President stressed Iran’s economic woes are linked to its relations with foreign states. With this gambit, the President set the tone for Iranian businesses going international. Iranian companies have the choice of two approaches to enter the international market. That is, either join the global supply chains or jump in on their own. The first is a low-cost, low-risk, low-value approach that can pave the way for growth. The other involves tremendous competence, risks, costs and competition against established supply chains. Iranian response to sanctions in its “resilient economy,” later redubbed “look to the east” policy has, therefore, a fundamental problem; the foreign policy is exclusionary, cutting ties of domestic businesses off the global north and there are many businesses in Iran which, one way or another, have stakes in those connections. A reversal has happened here. Historically, the adversarial, more powerful state is the one to cut off the ties to the detriment of its own businesses. Here, Iran’s exclusionary policy has angered businesses with ties to the global north who have logically opted for the low-risk, low-cost approach to international market entry. While the policy would garner support from domestic businesses of low-value activities, especially in the supply chains headquartered in the south, it did collide with the businesses with ties to global supply chains which are predominantly in the north. The government inevitably used coercion against the latter to manage the misalignments. We should note that the measures of supply chain ownership in the mainstream are mostly misguided. For example, the US, especially during Trump, speak of GDP and trade deficit to propagate its political policies against China. This is while GDP is an annual measurement but it is the cumulative that is of importance. In trade deficits which are based on gross exports, for example India or China’s exports in Apple electronics are cited even though of the about 300$ manufacturing price less than 10$ belongs to these countries. So, who controls the global supply chains is of significance and it is not what is usually depicted in the media. The global north, as shown in the table, controls the majority of global supply chains even though they only accommodate 13% of the world population.

Table 1: Global supply chains and Iranian connections. Own study. Data from OECD and Iran Ministry of Industry

The Iranian government’s uphill battle is against the businesses since once they become high-value, no matter their original alignment, they will look to either join or control global supply chains. They then might collide with the state’s foreign trade policies. On the other hand, high inflation means low-value activities are barely desired, even if the production costs, excluding risk premiums, are still competitive internationally.

Given the inroad in the coalition government of the camp who advocates for joining the global supply chains of the north, we could expect that many dormant, new and established connections in Iran to these chains will surface in the short-term. However, the rewards will not be widespread and this outcome mostly benefits those closest to these players. We also expect that the government will harden its stance on social freedoms, especially those that coincide with what it calls western values. Consequent of the limited radii of economic benefit and burgeoning social limitations, the general business environment will suffer from migration of skilled workers, and the domestic market itself will not be attractive enough for the import of consumer goods in scale. However, owners, managers and employees of low-value domestic businesses and businesses linked to the global supply chains will benefit and there will be even a monetary cascade that will eventually go through their domestic supply chains. For at least a small window of time, there will be a frenzy of activity from inside Iran in both linking to global supply chains and upgrading domestic infrastructure. Businesses have to pick a camp, if they have not already, and ensure they have the competence and connections to use the opportunities that each camp within the coalition government is willing to offer.