By: Asal Taheri

HIV may be one of the most common viruses in the world, but it still carries the heavy weight of incurability. Affecting approximately 38 million people worldwide, this virus remains a global challenge, often shrouded in stigma and fear. While antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV from a life-threatening condition into a manageable chronic illness, it’s essential to recognize that there is currently no cure. ART can suppress the virus to undetectable levels, allowing individuals to lead healthy lives, but if treatment is interrupted, the virus can reactivate from hidden reservoirs within the body. Yet, amid these challenges, a beacon of hope is emerging. CRISPR gene editing technology is paving the way for a possible functional cure for HIV. To grasp the potential of CRISPR in targeting HIV, it is crucial to understand the virus’s complex life cycle first.

Life Cycle of HIV

All viruses need living cells for their pathogenicity and replication, and they die after a while outside them. Generally, viruses first enter the cell and then use the cell’s resources like a parasite to replicate themselves. Eventually, new viruses exit the infected cell, infecting other cells, and this cycle repeats. What happens when HIV enters the body? We said that the virus cannot replicate without a cell, so it searches for a suitable cell to replicate within the body. The appropriate cells for this are the helper T Lymphocytes or CD4-positive cells. CD refers to a series of structures, usually proteins like antennas, that exist on each cell, and we identify and recognize those cells based on those antennas. It’s like naming cars based on the shape of their antennas. This CD4-positive T Lymphocyte’s function is to stimulate and assist other white blood cells in eliminating invading microbes and cancer cells. HIV enters these cells, replicates inside them, ultimately destroys them, and then new viruses target the remaining cells, and this cycle repeats.

HIV needs a door to enter its target cell. There is a protein called CCR5 that serves as an entry point for HIV. HIV first attaches to the CD4 receptor and determines this is the correct cell. Then, it connects to CCR5, opens the door, and enters the cell. One of the methods for treating AIDS is to block this door. By blocking this door, HIV cannot infect its target cell. Based on this, the drug Maraviroc was developed, which acts like a lock that closes CCR5 and prevents HIV from entering. After the virus enters the cell, it must prepare to utilize its resources and live parasitically. The genetic material of HIV is single-stranded, while our genetic material is double-stranded. After entering the cell, HIV performs this conversion. For this purpose, it uses its reverse transcriptase enzyme to convert its RNA into double-stranded DNA, which resembles the genetic material of human cells.

In the next stage of HIV life, after its genetic material becomes double-stranded and turns into DNA, this virus integrates its genome into the immune cells infected using another enzyme called integrase. At this point, neither other white blood cells can reach it, nor can the drugs! This is one of the main reasons we have not yet been able to create a definitive cure for AIDS. Its hiding in the genetic material of the nucleus of millions of white blood cells is a significant factor. Once the HIV genome enters the human genome, HIV can immediately start producing new viruses like itself, or it can remain there for years and then become active.

Why Is It Difficult to Create an AIDS Vaccine?

The first question that arises regarding the AIDS vaccine is why, despite all the advancements in science, the AIDS vaccine has not been developed yet. Why can’t we produce a vaccine similar to the Coronavirus or others that stimulates the body to produce antibodies so we don’t get infected anymore? In summary, HIV is much more advanced than other viruses, and it is not easy to design a vaccine for it like for others. However, scientists have made progress in this area. The role of vaccines is to stimulate the immune system to produce neutralizing antibodies against pathogens. However, the problem with HIV is that its stimulation is very low, and white blood cells cannot recognize it. Let’s assume you had a parrot that flew out the open window and got lost; the parrot here represents the HIV that the immune system wants to find. You want to do it by writing a paper notice, which becomes the immune system’s antibodies to find HIV. You also become the white blood cells in this example.

If the parrot’s color is only red, you can probably see it and easily find it from that window. If it’s multicolored and that city is full of parrots, finding it becomes more challenging. But by putting up an advertisement based on its color pattern, there is hope to detect it. But what if the parrot changed its appearance every day? That’s why scientists haven’t been able to create a regular vaccine for HIV. Scientists are working to develop vaccines that stimulate the body to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV or that allow us to make these antibodies outside the body and inject them into patients. Much research has been conducted on this subject, and some have even reached the stage of human trials. However, no approved vaccine in this category has yet entered the pharmaceutical market.

Gene Therapy

A gene is the information that constructs everything small and large in a living organism. A gene is a complete book describing how a creature is made. In gene therapy, we try to treat diseases, with our focus here being HIV, by altering the genetic material of cells. If we can make white blood cells such that HIV cannot enter its target cell, or if it does enter, it cannot replicate it, we will have achieved our goal of a definitive cure. Alternatively, if we can locate and eliminate the hidden HIV gene within our genome, that would also be beneficial; after all, being able to extract even a strand of hair from a bear is a gain. For now, the first promising method in gene therapy is CRISPR.

CRISPR

CRISPR is a method that allows us to cut DNA, or the genetic material of cells, from anywhere we want. As mentioned, the HIV genome hides within our genome using the intergrase enzyme; now, with CRISPR, we can identify and remove the virus’s genome from the DNA. Essentially, CRISPR is based on a definitive mechanism that bacteria use against viruses. Some bacterial viruses also hide themselves within the genetic material of bacteria, and the bacteria use enzymes to remove these viruses from their genome. With the invention of CRISPR, we can find those HIV gene segments and remove them from the genome, or wherever the HIV gene is, whether inside or outside the cell, we can disable it by cutting it out. This way, that cell is no longer infected with HIV. However, we have one problem: we have millions of infected cells in an infected person’s body, and we need to eliminate the infection from all these cells. If even one cell remains, it can still cause infection. A possible solution for this issue is to take the patient’s bone marrow cells, use CRISPR to delete the CCR5 protein gene, and inject them back into the patient. This way, their bone marrow produces white blood cells that are resistant to HIV. With CRISPR, we can force the hidden virus to emerge from its hiding place in the genome and eliminate it with existing medications.

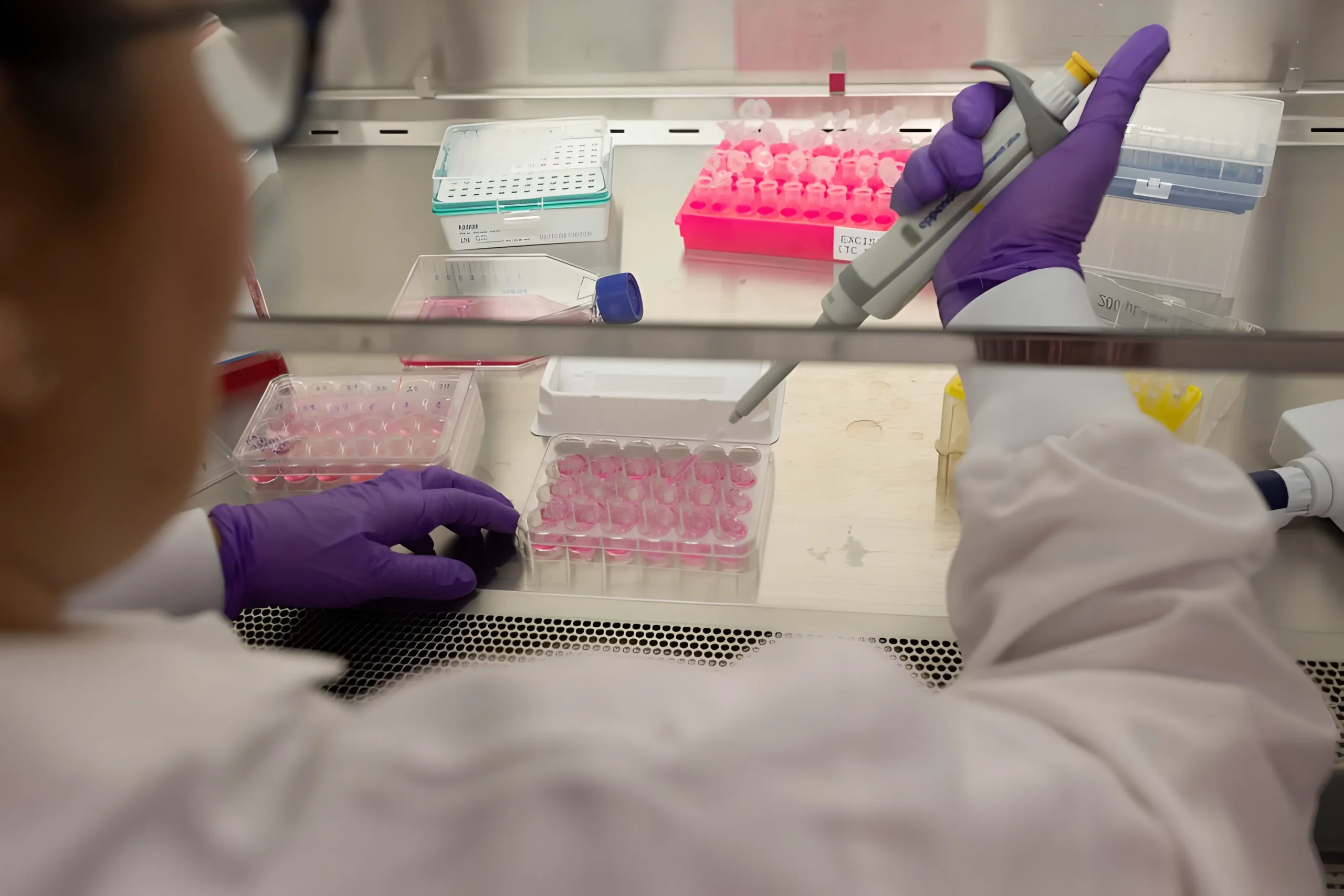

Clinical Trials with CRISPR

According to the recent updates from clinical trials, scientists have tested the EBT-101 gene-editing therapy on five patients as part of initial trials. Researchers at Temple University’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine developed this therapeutic method. EBT-101 is an innovative, in vivo CRISPR-based therapeutic candidate designed to excise HIV proviral DNA from infected cells. This therapy utilized a single intravenous infusion of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver CRISPR along with dual guide RNAs that target three distinct sites within the HIV genome, aiming to remove substantial portions of the viral DNA and reduce the risk of viral escape.

As of December 2024, early results indicate that two out of these five patients showed a significant reduction in viral loads after receiving EBT-101 treatment without needing continued antiretroviral therapy during follow-ups. The trial, which is open-label and sequential, primarily assesses safety and tolerability while also evaluating pharmacodynamics and biodistribution.

In addition to these findings, a recent update from the trial reported that all five patients experienced mild side effects, such as fatigue and transient fever, which resolved without intervention. While three participants who halted antiretroviral therapy experienced a rebound in viral loads, one patient maintained suppression for 16 weeks post-treatment. This patient has been closely monitored for any signs of viral rebound.

Furthermore, researchers plan to extend the trial to include additional participants to better understand the long-term efficacy and safety of EBT-101. The next phase will involve a larger cohort and assess the potential for combination therapies using CRISPR alongside existing antiretroviral treatments. These findings suggest a potential pathway toward functional cures for HIV, highlighting the importance of ongoing research in CRISPR technology as a transformative approach to HIV treatment.

5 celebs who died from HIV

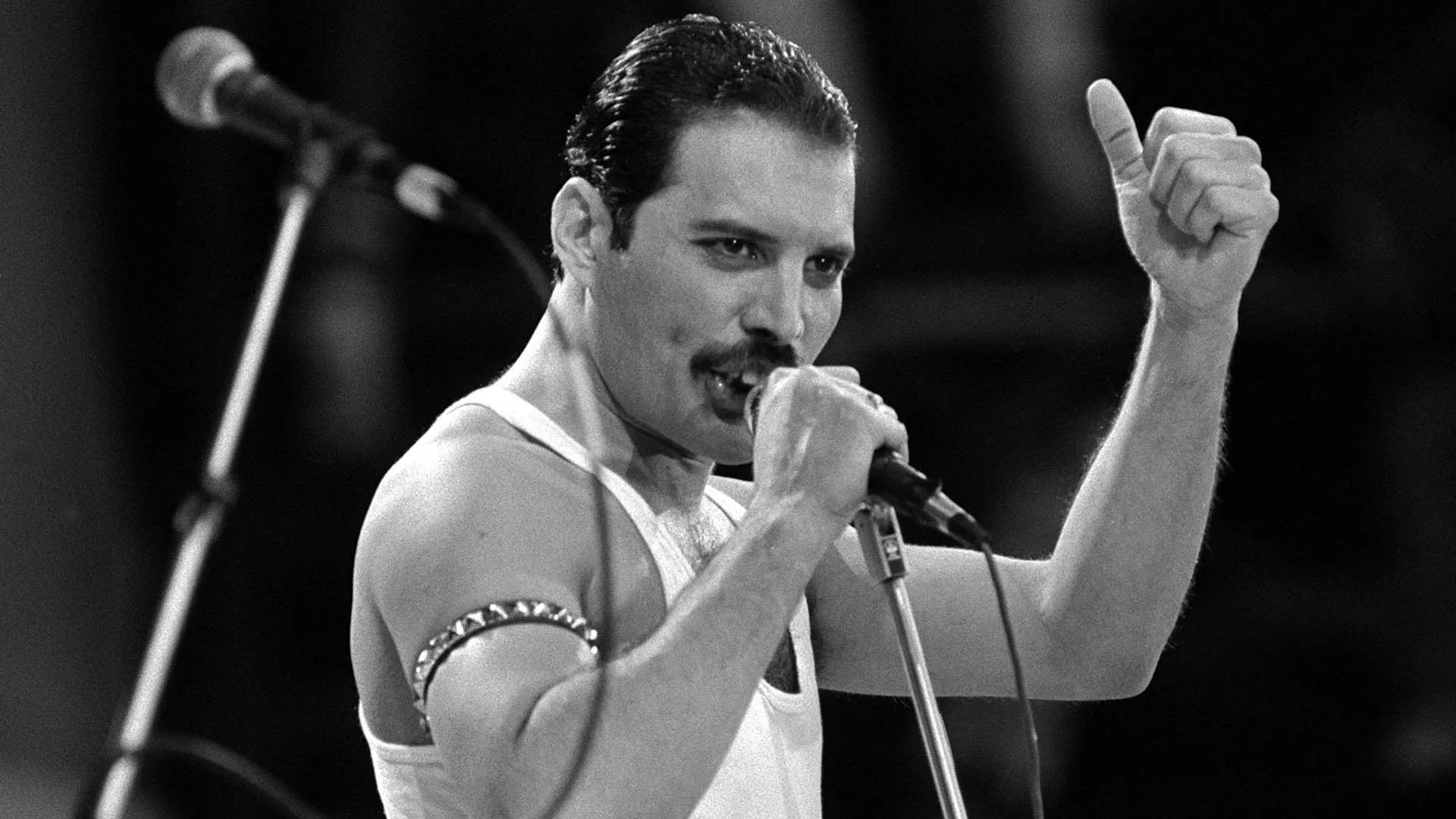

- Freddie Mercury

The legendary frontman of Queen was diagnosed with HIV in 1987 but kept his status private until just one day before he died in 1991. He passed away from AIDS-related pneumonia, leaving a profound impact on music and raising awareness about the disease shortly before his death.

- Eazy-E

Eric Wright, known as Eazy-E, was a pioneering figure in hip-hop and a member of N.W.A. He revealed his AIDS diagnosis just days before his death in 1995, passing away at the age of 31. His sudden illness highlighted the severity of HIV within the African American community.

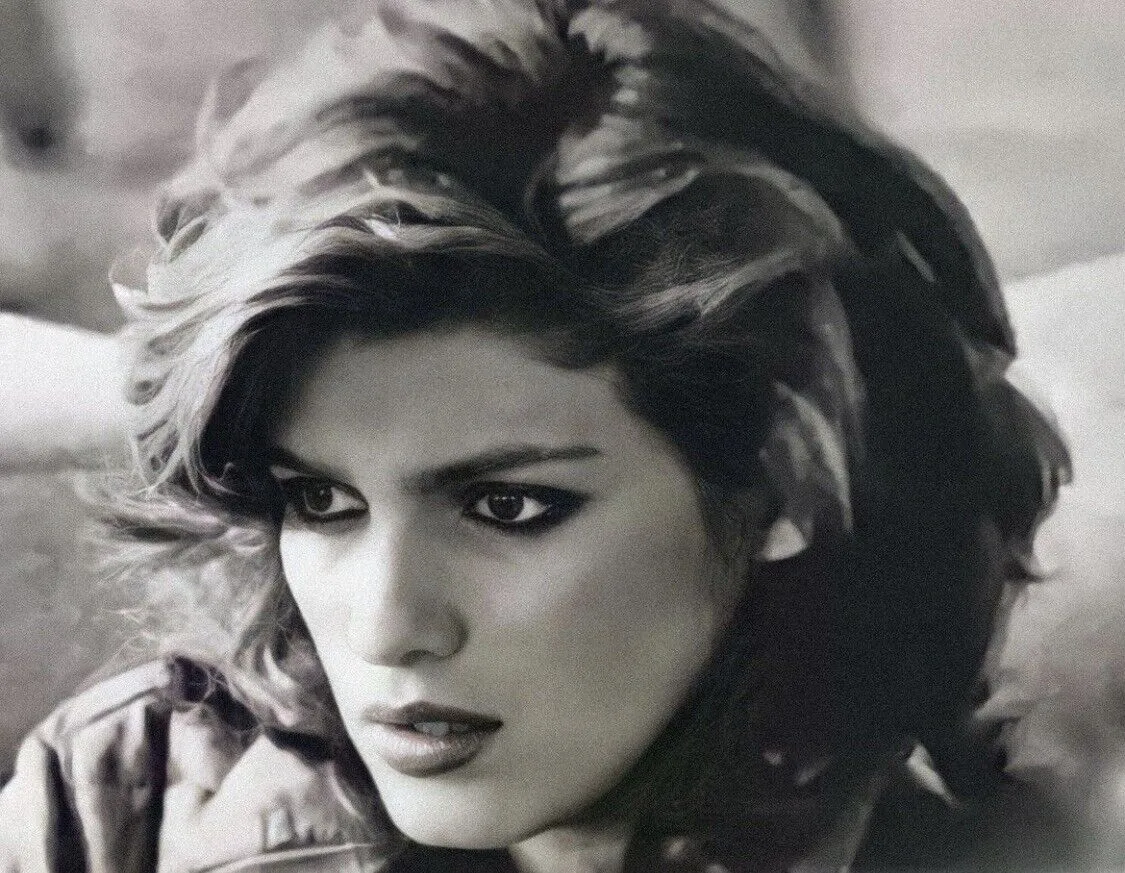

- Gia Cerangi

Often referred to as the first supermodel, Gia Carangi rose to fame in the late 1970s. She struggled with drug addiction and reportedly contracted HIV through intravenous drug use. Carangi died from AIDS-related complications in 1986 at the young age of 26.

- Rock Hudson

A major Hollywood star during the 1950s and 60s, Rock Hudson was the first high-profile celebrity to disclose his AIDS diagnosis in 1985 publicly. He died later that year from AIDS-related complications, which prompted increased awareness and activism surrounding the disease.

- Liberace

The flamboyant entertainer Liberace kept his HIV status private for most of his life. He passed away in 1987 from complications related to AIDS, and his passing raised questions about the stigma surrounding the disease at that time.

5 celebs who survived HIV

- Magic johnson

NBA legend Magic Johnson publicly announced his HIV-positive status in 1991, raising awareness about the virus. He has lived a healthy life for over three decades, attributing his well-being to effective treatments and a healthy lifestyle. Johnson continues to be a prominent advocate for HIV education and prevention.

- Charlie Sheen

Actor Charlie Sheen revealed that he was diagnosed with HIV in 2015 after living with the virus since 2011. He has since used his platform to raise awareness about HIV and promote safe practices despite facing controversies regarding his past behaviors. Sheen aims to support others who are living with HIV and reduce the stigma around the condition.

- Billy porter

Tony Award-winning actor Billy Porter disclosed his HIV-positive status in 2021. He has been vocal about living with the virus and aims to reduce stigma while promoting education on HIV/AIDS.

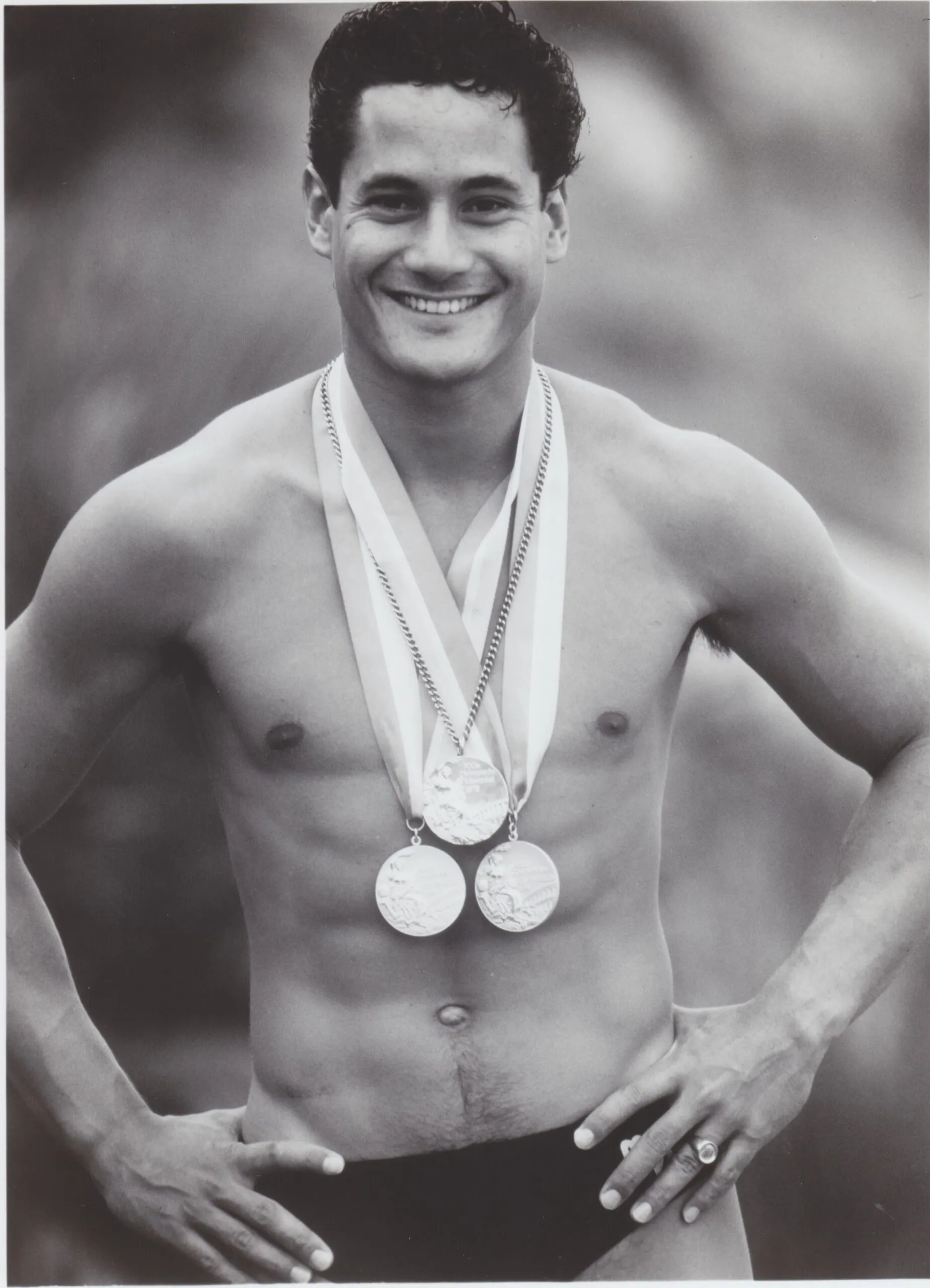

- Greg Louganis

Olympic diving champion Greg Louganis was diagnosed with HIV in 1988 but continued to compete at the highest level. He publicly disclosed his status in 1995, becoming an advocate for HIV awareness. Louganis has worked tirelessly to educate others about living with HIV and has authored several books on the subject.

- Mykki Blanco

Rapper and performance artist Mykki Blanco came out as HIV-positive in 2015, revealing they had been living with the virus since 2011. Blanco uses their platform to challenge stigma and promote acceptance within the LGBTQ+ community, emphasizing that an HIV diagnosis does not define one’s identity.