By: Farid Atighehchi

In Tehran, neither the movements in the market nor the prevailing mindset projects a full-fledged JCPOA revival before the next US administration. If history is any lesson, as in the 1979 hostage crisis out of fear of another USlead coup or the US reneging on a backdoor prisoner swap agreement in the 1990s’, the Iranian state would prefer to linger over negotiating a new compromise. All the while, Western analysts fail to mention that, even though a nearing sunset clause may not be ideal for them, any economic impact out of a deal for Iran takes even longer to implement, let alone see the results. Movements in the market echo this sentiment. While prior to the original JCPOA the market was buzzing with preliminary negotiations about trade with the West, talks now have not been but with the Russians and other opaque or small economies mostly to the East. Since this issue of Trends has a focus on Latin America, in this chapter of Iran Economic Outlook we also briefly touch upon the opportunities of trade there, taking a broad view of few industries in better shape to engage in exports. However, before that, we note some economic developments.

Majid Hariri, head of Iran-China Chamber of Commerce, argues the state’s new position

against the private institution goes counter to laws and rationale. He identifies the date

when this course started conspicuously as 2014.

Consumer Price Inflation

Despite the government’s insistence on curbing inflation and barely a year after it assumed office, some of its own officials are starting to criticise its plans as inflation-inducing, especially pointing to cash subsidies to people instead of businesses. Some officials are anticipating short of 50% yearon-year inflation by October. Observations in streets more than corroborate this projection.

Uncertain Fate of Chambers of Commerce

The grounds are being laid by the government, as mentioned in previous notes, to turn maybe the most democratic institution, chambers of commerce, into public institutions. Even though it was already heavily influenced by statealigned traders, their elections and administrations have not been directed by the state. However, the state continues to undermine this institution in two ways: it is restructuring its own relationship with the chambers, and is intervening in its democratic mechanics. We could expect that the chambers of commerce will soon be assimilated into the state, even if not the government, and will explicitly and directly represent the interests of the parastatal and the central government rather than individual businessmen and their professions, although its representatives prefer to be called “private.” Among other things, we will not hear again, for example, the Iran Chamber of Commerce question the economic feasibility of an agreement with Russia to swap gas from Azerbaijan.

Gholamreza Nuri, MP, suggests the government will keep its hands off chambers of

commerce. While the parliament’s own Research Centre advises that transforming the

institutions to public entities defies their purpose and legal definition, the MP’s voice seems

to get lost under the roar from his peers and the state.

The 7th Development Plan

The five-year development plan comes into effect in 2023. It targets an average annual growth rate of 8% and is about technology, efficiency and paying for the government from taxes. While the details are yet to be announced by the government, the publicized outline fits the pattern of developments and policies we already see in the works.

Demographic Shifts

Brain drain has long been disconcerting in Iran. However, it has reached disturbing levels recently. Notable among the migrators are engineers in the government or the parastatal firms, and physicians. Their reasons, and many others’, range from government’s shrinking bonus packages to dividing social policies that put people against each other in violent ways, which also disrupt everyday business operations and raise the risk of civil unrest, itself a key factor in foreign direct investment decisions. Those who remain are the patriarch of the political elite and rentier business owners who can already afford long holidays and living in advanced economies, lower-middle and lower-class citizens who may opt for the resulting vacancies, and a growing army of political soldiers who swamp every profession, heavily subsidized and tasked with producing offspring.

This demographic change will have certain consequences for the economy. While Iranians are not technologically advanced enough to manage complex production efficiently at a large scale of commercialisation, the existing levels of manufacturing, service, and maintenance, still largely rely on the technical knowledge of workers. The demography of production, thus we could expect, may turn to favour assembly of less complex components, or simply end in steep efficiency decline. It may also mean that producers would struggle to maintain competitiveness against imports, let alone in the exports market. This could work for traditional businesses of trade and mercantile networks who have assets in production as well and could switch back to imports readily. If that is the case, then we will see, in a year or two, the competitiveness scores collated by the government, UN and other observing bodies would reflect such effect.

The impact of this change on international trade, such as receiving outsourcing deals, would be limited though, as existing issues with manufacturing efficiency and cross border investment flows are prohibitive. The demographic shift would also mean different tastes and purchase behaviour emerging as dominant. The ordinary lower middle and lower class are focused on a basket of goods of essentials, the growing subsidised army have politically motivated culturally peculiar purchasing behaviour, and the affluent may be a somewhat negligible segment in most product categories. This would call for repackaging value offerings.

The anaemic demographic composition would fail exports but not completely. There would be product sub-segments and companies, even if in smaller numbers, that can maintain some competitiveness. There isn’t only one way that these companies are able to stay ahead of their economy. Among them are established business owners, either politically favoured or in greyer markets, that are innovative with their business models.

For example, adopting an ecosystem-based model is helping some to redistribute their production across borders and rebuild their advantage around their technical experience. Others are repositioning their products for an environment that no longer offers the same level of sustenance for the same activities.

Forouzan Abdollahi, Chairwoman of Engineering and Construction Companies Association

in Oil and Power Industries, warns Iranian OGP is losing its skilled labor in a rate that is

crippling EPC work.

Industry: Electronics and Optics

Since the US sanctions returned, imports of home appliances have been stopped to save cash. On the other hand, the government also curbed price rises as the products are a large part of the consumer basket, along with housing which the government does not effectively regulate. As the East Asian and European brand names that middle class households were used to were no longer available, manufacturers and imports-converts flourished. Home appliances, with trade association alone accommodating about 250 companies, suddenly jumped in production in 2020. That habit of buying quality for home application is why all the new Iranian identity designs somehow resemble original brands such as LG and Siemens and even, weirdly, since there is no brand awareness in Iran, Dupont.

The same story has been happening with medical equipment. A market that previously largely relied on imports, is now a manufacturing industry. Medical equipment players have long been among the most disciplined and most private. This is one of the few subsectors that has survived the recent economic shocks with relative ease. In the vast array of highly technical products that make up this market, there are still many, namely more than half of all types, that are not produced locally. For those that are though, the results have been successful, and manufacturers feel confident they can export as well. Exports here have been around 24 million USD, at their highest, which is quite an underachievement, given that the manufacturing capacity is currently beyond

that.

Industry: Electrical Products

For long, the steel industry and other extractive metallurgy operations have been Iran’s pride or rather prejudice. Here furnaces are big and take the spotlight. Along come electrical transformers as one of many key components that keep them burning. As US sanctions intensified after Trump, the Iranian steel industry had to resort to procuring the transformers that used to be imported from Europe, especially Italy, through domestic production. For that to happen, local manufacturers had to transfer, buy the license, or reengineer the technology needed for the application

And the results are being applied. Transformers are among simpler components that rely on quality of design and manufacturing rather than a complex design of smaller components. With a huge source of copper and other minerals at hand, production in Iran is competitive. The same is true with electrical cables or many products that are used in the delivery and transformation of electricity. This is a category concentrated in Zanjan Province, which sells close to a third of all electrical cables, and Tehran, hosting the dominant, parastatal IranTransfo.

Nevertheless, their failure to reach an international market before local economic problems caught up, means plants not connected to the government to receive better orders or bailed out by their banking shareholders are working way below efficient capacities. Per trade association officials for example, electrical cables are being manufactured at 30% capacity. Other parts of the industry, such as lighting, may not be doing well, struggling with sanctions and poor performance of their suppliers and regulators. However, for the copper-based simpler components such as transformers

and cables, there is much room for growth and exports. Electrical motors, such as AC motors, seem to be experiencing a more dramatic story but they too are among those that, at least in volume, can support exports.

Industry: Base Metals

Production of base metals in Iran is relatively more developed than other industries and for good reason. Not only does it serve strategic industries, but the country’s geography supports its growth. Iran, for example, is among the top ten in discovered copper reserves globally, among countries like Russia and Chile.

This industry is tangled in regulations and politics as it supplies the key industries of steel production, car manufacturing and construction. It is also sensitive to energy prices, where electricity production has been problematic recently and energy subsidies are gradually being phased out. Still, its place in the strategic value chains usually translates into technological competency and large capacities that can readily service export orders.

Basically, a parastatal industry at its upstream, production is streamlined, but delivery may be tricky where managers are concerned with interest group politics and fleeting agendas, rather than individual business success. To the downstream, companies tend to be somewhat more private, and those which are not owned by parastatal entities and the political elite are subsequently easier to negotiate with and rely on in business terms. But then, regulations and policies tend to support larger, state-owned companies, which puts private firms in precarious positions.

There are times when exports may be more attractive to the industry, as in recent months when demand from major domestic buyers has waned but production is at capacity. This is an opportunistic view and is not reasonably predictable as all these factors, including ad hoc regulations such as a recent government ban on the exports of lead, make matters complicated.

Industry: Textile and Fabrics

Textile production in Iran has relatively low cash-flow problems and is, at the moment, well-supplied in its input material. However, this is a broad statement as it is a very fragmented market. Small producers are not positioned or networked to be able to export on their own. Larger producers, however, can handle larger orders. For many reasons, including an estimated 3% share of non-oil production’s contribution to GDP and 8% share of jobs in the country, many textile manufacturers have been owned by the state or the parastatal. This segment of the market relies heavily on preferential foreign exchange rates rather than business knowledge or competence. Consequently, they go on the brink of bankruptcy every time the government’s exchange rate policies interrupt this rent, and then they are bailed out. The industry has been shrinking over the years; the figures quoted above used to be 4% and 10% about a decade ago, but this is not an isolated event and has been along other industries failing to survive the harsh economic conditions. The affairs of the rentier group of companies here are too volatile for them to service international orders reliably, but private firms are numerous and offer a wide range of products.

Venezuela president Nicolas Maduro has visited an Iranian exhibition in the capital Caracas

which showcases the Iranian knowledge-based companies’ products as well as the giant

Iranian automaker Saipa group.

The industry suffers from outdated machinery. More than two thirds of all companies rely on equipment that is on average 30 years old and lags behind other industries in technology and yet, it supports 4% of the country’s total non-oil exports. Where Iranians have an edge though, is in polyester fibres and its products. Of all the demand for cotton, about half is imported but the petrochemical industry offers affordable polyester of competitive quality. However, exports have been underappreciated and not much work has been put into it. Iraq, India, Turkey, and Afghanistan are among the top destinations for different sub-segments of fibre and filaments. Woven and nonwoven fabrics have also long been an exporting sector, though they are struggling with new regulations regarding their input procurement. In the floorcovering segment, the industrial production is annually about 94 to 127 million square meters, where again Iraq and Afghanistan receive most shipments. This focus on bordering countries does not make sense for textiles and is out of ease, with the export seemingly coming from unsolicited orders by visiting traders in the neighbourhood rather than active foreign market entry efforts by Iranians. Looking at all subcategories, Isfahan stands out as the centre of the Iranian textile industry.

Industry: Paper

Paper producers have relatively lower cash-flow problems, and their input supply has been somewhat stable. They are also companies of a sweet size; neither too large to fall into political infightings over oligopolies nor too small for active international trade. The Iranian paper producers’ syndicate alone is about a hundred members strong. In the past few years, production has been on the rise and many of the input materials, such as dyes, that used to be imported, are also now produced domestically in sufficient volumes to meet local production needs.

The entire industry is about 5.5 million tonnes. However, it suffers from old technology. In tissue paper, businesses mostly cut, and package imported sheets. In printing and copier paper, Iranians produce straw papers and only enough to meet half the domestic demand. Many large producers in Iran manufacture liner and floating papers, about half of all the paper production. Hence, it is in cardboards that this industry may be able to serve growing orders.

A Hispanic Story

Despite the recent obsession of American political organisations, the Iranian outreach to Latin America is extremely limited. In fact, there are more Iranians living in Finland than in the entire South America. However, there are opportunities for trade here for those who are willing to take them.

During different Iranian administrations, the governments’ approach to facilitate trade has barely gone beyond the superficial, mostly focusing on diplomatic incidents such as those exemplified in the 2013 Argentina-Iran joint investigation into the AMIA terrorist attack, Iran’s petrochemical investments in Venezuela, and the recent seizure of the Venezuelan-flagged Boeing in Argentina. In

the absence of successful government delegations in the continent, the burden has been on the private sector to solve any issues and stay competitive. This has made imports much easier.

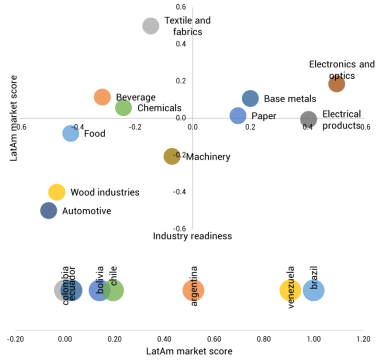

Here however, we looked into how a select group of South American markets score in terms of opportunities of exports from Iran. A multitude of factors were adopted, ranging from coinciding votes in the UN general assembly to liner shipping routes and transportation costs to anticipate where Iranian products would be more successful. Brazil tops the chart, and this is not surprising, given that it has long been a key business partner of Iran in the area. We also investigated which Iranian industries are better positioned to export to South America. From among a dozen in better shape to engage in exports, textiles, base metals, electrical products, paper, and electronics are especially expected to do better. We also see that the recent inauguration of car manufacturing plants in Venezuela by Iran, for example, seems political in that it is big, governmental and provides optics but is probably not economically feasible. And, as another example, while Iranian paper is relatively competitive, Brazil is a top exporter in the world. These examples show there are nuances in reading the chart and subcategory products need to be investigated individually for thorough planning. Iranian chambers of commerce and government have recently held many meetings with their South American counterparts and companies to further explore the possibilities. There are other venues as well, such as trade fairs and conferences. And of course, at the end, nothing works better than a direct call and a visit with a possible partner. To say that trade between South America and the Middle Eastern mediumweight is a missed opportunity is a gross understatement. Businesses could take advantage of the gaps if they joined in the conversation.

LatAm Market Score

Figure 1 Position of select Iranian industries for exports to Latin America. Own study. Combining 4 measures for industry readiness, including those indicative of cash-flow problems and market fragmentation, while market score is made up of 20 measurements across 7 markets, 35 HS codes and economic, political and business categories. This is based on a coarse view of both the industries and the markets and should vary in sub-segments.