By: Farid Atighehchi

It would be a perverse study of the economic outlook of Iran if we ignored the elephant in the room; the recent civil unrest sweeping across the country. In business circles, people are constantly assessing the situation, from the probability of JCPOA revival to the state’s stability in the face of a popular uprising and what all this means for economic activity. Ideas and comments show a desperate hope that any new development will somehow end in a positive outcome despite the prevalent feeling of doom and gloom.

The question that guides business decisions now is if the deteriorating economy, especially the rise of poverty and ensuing discontent in the masses will lead to state failure. Additionally, we may ask what that means for the individual business and its survival. Let us start by finding the cost of the internet disruptions since September.

Economic Impact of Internet Shutdowns

Calculating the economic impact of the internet shutdowns and interruptions since late September 2022 until early January 2023, shows that about 23 billion dollars’ worth of business has been negatively affected. That is to say, using a crude estimate, that magnitude of economic activity has faced problems such as delayed communications, delayed deliveries and delayed transactions. The actual losses may be less or more than this number. A more certain estimation, only accounting for fully-online businesses, shows a minimum of 2.3 billion dollars may have been lost.

Iraqi Prime Minister replaced the country’s Central Bank Governer, Mustafa Ghaleb

Mukheef, in January. Mukheef were allegedly at odds with Iranian aligned forces and against Iranian monetary ties in the Bank.

Therefore, the losses may have been anywhere between 21 to 210 million dollars a day. When we put this number against the poverty line, per official and semi-official statements at 360$ per month per household, it shows that a minimum of 430,000 household-years has been lost –that is a loss worth the annual income of 430,000 households in 2022. This number may easily be in the range of 4.2 million household-years. At the time of writing this essay, internet restrictions are ongoing, with communications over the internet, especially on mobile phones, reduced to a bare minimum of basic services. And so, the loss making is continuing. Per different estimates, up to 13% of the households in Iran directly rely on income generated over the internet. It is noteworthy that, based on speculations of the volume and known prices, Iran sells about 70 million dollars of crude oil per day. On average, internet shutdown has cost Iran about the same amount as its oil exports. However, while comparing the value of losses, we should remember they are not incurred by the same people. This disruption may seem part coercion and part punishment but, as the state transfers this cost to the working population, the economic impact actually benefits the stability of the state –that is, while the state contains the discontent.

The Makings of Discontent

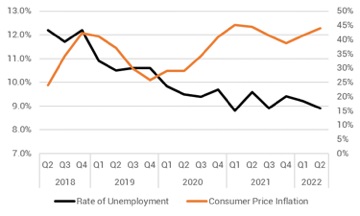

Official statistics put the consumer inflation at more than 45% in 2022. A sustained, high inflation rate over the course of the past few years means that the prices of, for example, food basket has increased by more than 4.3 times since 2018 and risen by 68% since last year. This is while the income of the working class does not rise at this rate. The official consumer price index reflects the realities in the market but with limitations. Especially one could argue that the weighting the government uses in its calculation is not very appropriate. In summer 2022, the last data published by the Statistics Organisation shows the number of unemployed at 8.9%. We have no way of verifying if this number is accurate. What is clear is that it is becoming increasingly difficult for the ordinary people to make ends meet. The policies and interventions of the state, for example in real estate, energy and financial markets, predict higher consumer inflation in 2023 than many previously expected, namely over 50%.

Rate of unemployment& Costumer price inflation

Rate of unemployment& Costumer price inflation

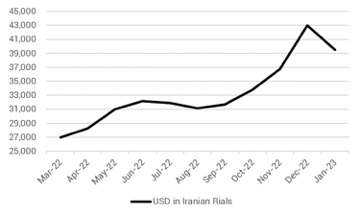

What made the biggest splash in the market and among businessmen and other people was the drop in the value of Rial, especially as the protests started and began to gain momentum and also when it became much more apparent to people that the prospects for the revival of JCPOA is bleak. In less than nine months since March 2022, Rial lost a third of its value against the US dollar, and other major currencies. Keeping Rial increasingly looks like a hazard to a terrified population. That is one reason cash is now scarce as people try to convert Rial to other assets, from foreign currencies to cars to real properties.

Climate change and mismanagement of environmental resources is also putting pressure on people. There are official plans about an upcoming “water market” for drinking water. For a country with widespread infrastructure and, so far, very high access to drinking water across its urban and rural areas, this is grim news. The question is if these and other social, economic and political woes would turn polarisations to larger civil unrest. And will they tear into the institutional fabric of the state?

Morteza Farrokhi, Undersecretary for Legal and Parliamentary Affairs, issued a memorandum

to universities across Iran in January to send their list of academics who should be allowed

to access the “open” internet.

Political Economy of Protesters and State

It is easier to take averages when, for example, we talk about purchasing power parity but the allocation of resources is anything but a normal distribution in the current Iran. The state is an oligopoly that controls most of the economy. If the economic situation were to deteriorate, it would not deteriorate for all equally and therefore would not destabilize the system altogether. Trouble would come if they were to threaten the institutions, which have shrunk in number in mergers and hostile takeovers just like businesses.

These institutions spawn new political positions that incentivize lower echelons of power to offer support and extra work. Many different “councils” as well as lower-level “committees” in the past decades could be named as testament to this practice; there seems to be close to 3,000 state agencies and bodies and more than 12,000 semi- governmental companies in Iran while, for comparison and according to Forbes quoting a US Senator, there are 430 departments, agencies, and sub-agencies in the US. The state may have found that it cannot create further positions at a national level. It would then try to organise the competition at lower levels. The upcoming pseudo-federalisation formalises the career paths of the state agents locally. This would mitigate the negative effects of the slowed economic growth on the support the state receives from its agents. Meanwhile, the increase in inequality makes the prospect of a bureaucratic career even more attractive because the stakes for state agents become even higher where they can apply and work their way up the ladder to eventually get rents.

Soon after the writing of this article, the news came about “movaledsazi,” a decree from the Supreme Leader,

officially agreed between the heads of the branches of the government without going through the usual channels,

and with the Supreme Leader giving full immunity to the committee that is to carry it out.

The state also needs safety valves. For example, a part of the former middle class used to be bureaucrats, some of whom made it to the top but some were not promoted despite their loyalty. For those rejects, there has been a smaller reward: retirement in an advanced economy. Where the state cannot repay its agents in form of rents and higher positions for their diligent work, they are offered a retirement abroad. A noticeable number in the Iranian diaspora in Europe are former state officials and their families.

This formalisation at the local level, still unfamiliar for the agents, combined with the economic uncertainty, would push them to not only intensify coercion of the working population to maintain inequality, but also to extract more labour from them to further their prospects of promotion. The pseudo-federalisation and a council of leadership replacing the position of the Supreme Leader, both ideas increasingly propagated around on social media and on the street, would keep the existing hierarchical system of the Islamic Republic safely in place. The state seems to have already been able to start this process, as evident in the budget of 2022.

This political reordering of the economy renders the purchasing power parity or the discontent of the working population irrelevant. From the state-dominated start-up community to government-sanctioned pop music events and film festivals, the state tries to provide ways to help some let off steam but it may be inadequate still as we see more frequent demonstrations. The recent protests however, while large in number and unified in theme, do not seem to have reached a critical mass of supporters to physically threaten the state. The fate of the state will be determined by a balance between its safety valves for the labourer and the level of inequality it wishes to maintain.

As for the middle class, we could expect government policies to further increase inequality in favour of the ruling class, while growth stays sluggish by incompetence and misalignment. A middle class may be emerging out of a new generation of state agents though. For this new group, consumerism may still be a political taboo and their population may be lower than the old one which was growing in size and expectations of reform but they will sustain part of the consumer market that has been eroding recently. This re-emergence of middle price ranges in the market should be visible in the next few years.

Meanwhile, a larger proportion of people are thrown into poverty or are at its precipice, prompting lower consumption in the market. While this means less sales in the mass market, the widening wealth gap and Iranian working class becoming poorer will not probably reflect in the GDP. Nonetheless, a sluggish economy may undermine the loyalty of state agents.

Foreign currency Exchange Rate in Rial

Foreign currency Exchange Rate in Rial

Assessing how some of the major contributors to the GDP are doing is a clue as to how successful the state will be because if its major economic lifelines are threatened; it might lose the support of its agents. We should ideally look at the financial services, oil and real estate but here let us suffice to briefly review the latter and see if it will collapse.

There is a gigantic bubble in the real estate market of Iran. Property prices across the entire country, and not just in Tehran, usually surpass those of global cities, are only short of those in Monte Carlo and easily rival New York and Paris. It does not take a genius to see that cannot be right. The bubble is a production of the banking system. Banks are expected to offer lucrative credit lines to state agents in many different situations. These loans are not paid off and the banks need to compensate for the negative impact on their balance sheet.

They do so by selling and repurchasing their real estate assets at a spread. This story is repeated every single day, in large numbers and continuously. The result is an asset price inflation far from the fundamentals of the market. The government also helps inflate the prices in its direct interventions. For example, in the backdrop of continued efforts to sell housing in parcels of square meters in the public market, the government recently announced it has the central bank offer stocks to individual banks.

Undersecretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence at the US Treasury, Brian Nelson,

Visited the United Arab Emirates in early February and shared “Treasury’s focus on rooting

out evasion of U.S. sanctions, particularly on Russia and Iran, and its commitment to take

additional actions against those evading or facilitating the evasion of sanctions,” reads a

readout from the Treasury.

The banks then would sell the stocks on the Tehran Stock Exchange in order to fund the “national housing programme.” They would be the benefactors in a “programme” where the state is the real estate developer and production is through contractors who barely share ownership, receive lower in monetary terms than in a private setting and are instead expecting rents. It has already gathered a huge market of contractors, while there is an exodus of established, private developers. The result is that the banks would benefit from revaluating their stocks and the price of properties irrelevant of fundamentals. This will prove a huge expansionary operation and will result in much higher housing prices without much actual supply of housing to the market. A number of factors, from the importance of offering loans to state agents to the rising consumer inflation independent of housing prices, leads to the disproportionate significance of this sector. It both employs a large number of people and attracts a large share of investments.

The sector is highly fragmented and with so many stakeholders, with both the owners in the working class and the state benefiting from the continued rise of prices, neither wants to see the bubble burst. Although the benefits for individual home owners are deferred –that is their equity is not liquid– while the state’s, through the banking system, is. With the banks playing as both suppliers and buyers and with no financial derivates built on real estate, the chances for destabilisation in this sector is suspect. Unchallenged, real estate continues to sustain the state and its agents.

The same goes for financial services. It also looks good in oil, gas and petrochemical sector as well. For example, Iran continues to sell its oil despite the sanctions. While there are no official statistics about this trade, estimations are about one million barrels per day for prices sometimes a good $8 above Dubai. If and how the payments come through may be irrelevant as the oil income feeds the ruling class and it is only when it is depleted that the mass market would feel an indirect pressure, usually in the form of more taxes.

Ali Shariati, member of Iran-Iraq chamber of commerce, speculates if Iran is printing money

Ali Shariati, member of Iran-Iraq chamber of commerce, speculates if Iran is printing money

backed by the assets frozen in Iraq.

As long as the population who enter the bureaucratic path looking for rents dominates the discontented masses and, more importantly, as long as the state can honour its promises to its agents, the costs are borne only by the working population and the state stays put. Sectors such as real estate and financial services could be artificially inflated, exploiting the working population and outside the reach of the sanctions. Also, the pseudo-federalisation plan not only does not undermine the system or mean reforms but it will strengthen the prevailing institutional arrangement. In the transition, there will be reshuffling of state agents, hurt feelings and targeted attacks.

There will also be chaos, failure and fatigue in business. However, the values, rules and rulers will stay the same. Old theories are never disproved. Businesses will need to adapt and abide, and the masses could either pay up and join the party to get wages or promises of promotion or they will suffer on the peripheries.