Turbulent Supply Chains

While agricultural production has been steadfast, despite everything, industrial activities and services have had compound problems. Fairly put, agriculture was relatively spared from job insecurities and market contraction. It, however, shared several huge problems with industrial manufacturing and services.

The almost constant impediment throughout Q2-Q4 has been imports of inputs, such as fertilisers or pesticides. A wide range of supply chains were disrupted by restrictions on imports, as CBI introduced firm quotas on foreign currencies and the US sanctioned all trade to the point of stopping ships physically.

Consequently, IRR exchange rates fell to the point that government had to intervene in various points across value chains to help with supply or to put a cap on prices , while raising taxes. Some industries even found the cost difference between imported supply and their end prices so high that it made much more sense for them to sell their purchased intermediate products instead of processing them into finished goods. And, naturally, chronic issues such as corruption and preferential treatments became more conspicuous, and more painful.

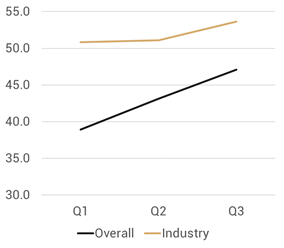

Purchasing Managers’ Index, 2020/Q1-Q3, Iran Chamber

of Commerce

A close look at the Purchasing Managers’ Index reveals the frustration in the market and how sales prices trailed input costs. However, despite all the hardships, the index has moved in a rather healthy band between 40 and 50. This could partly explain a lower GDP contraction than previously projected by the IMF. Still, CBI’s governor hopes for a better performance by April, something that is hard to achieve at this point. The problems began to appear around February and March, as the pandemic started to feel real. It exacerbated a budget deficit made by dropping oil exports, itself a result of US sanctions, and currency devaluation and imports issues, also inflicted by the sanctions. The CBI and government together introduced quotas on foreign exchange and while they could not resolve chronic problems altogether, they did try and support alternative possibilities, such as local production.

As we enter 2021, the state is easing restrictions on imports, albeit only minimally. Its prioritized budgeting also targets key developments. While there will be nuances in how the next administration coming in spring of 2021 will manage, the long-term policies, including a focus on manufacturing cars, petrochemical and steel will remain strong, and these industries can be expected to grow and see continued capitalization. But the prospect for other industries may be less than bright, and their profitability may fall below historic averages.

How Much the Corona Virus Hurt Iran

Iran expects the public roll-out of the coronavirus vaccine sometime between spring and summer of 2021. Everyone hopes to return to full normalcy once the vaccinations are in full swing, but Iran is already adapting itself to working around the limitations caused by the health crisis. The state seems to have performed well on par with the global average.

At Ara Enterprise, we started calculating the economic impact of the pandemic since July 2020. Our estimations cover the entire period since the onset of the pandemic in February. By early November 2020, the total economic impact of the pandemic caused by disruptions in supply chains and employment was 99 billion USD. That is equivalent to about 21% of Iran’s 2019 GDP. It is a major blow to all businesses, small and large. Individuals in the lower strata have especially felt the brunt of the impact.

The World Bank estimates a varying degree of poverty increasing across the country. Most notably people in Qom, Semnan, Qazvin, Markazi and Ilam provinces were to experience 15 to 35 percentage point increases in their current poverty levels. The state, of course, has provided relief for these households. The fact that recent GDP forecasts by the IMF show only a 5% contraction in 2020 goes to indicate the resilience of the Iranian economy. It may be that a tough discipline for efficiency and prioritised resource allocation has paid off.

The estimates cover the period February 1 to October

29, 2020. The charts depict the top five most heavily hit

industries within each sector

Nevertheless, the recovery will be rather difficult. That is because the tremendous economic pressure from the sanctions highly limits the possibility of introducing direct stimulus packages. So far, the government has not been able to do more than provide direct relief to households and small businesses. Without a stimulus, the onus of recovery is on fiscal and monetary policies and businesses trying to survive and innovate.

People Spend Less, Find New Sources of Income

The pandemic had its toll on business activities as cities large and small went through on and off lockdowns. To stay open, businesses have been grouped base on their prominence or importance to everyday life of residents, and different rules, schedules and curfews have been applied to each. The Ara research team could not independently verify the exact toll on employment and official statistics are yet to clarify the impact. The changes in spending were easier to follow, with consumer prices rising because of the sanctions.

Consumer price index from January to October 2020,

Statistical Center of Iran

As goods started to compete in price hikes and businesses were interrupted by the pandemic, many people moved to other or additional sources of income. Those who did not have enough savings to invest, tried instead to hang on to their jobs and even take on alternative jobs when possible. For its part, the government raised the minimum wage, trailing the inflation, from about 19 million IRR the previous year to around 35 million IRR in this calendar year.

It also distributed its small available funds among the unemployed and extended furloughs for its own employees. Furthermore, in lieu of a full-fledged stimulus package, it bolstered and expanded the existing programmes to save bankrupt businesses, and hence jobs, through the support and collaboration of the banking and judicial systems. Most of the loans disbursed to small and large companies stipulated the condition that they commit to keeping their employees. Despite these government interventions, the labour market has shrunk. Both the unemployment rate as well as the economically active population numbers have decreased by 0.8 and 1.2 percentage points, respectively.

While we cannot pinpoint the exact dynamics and situation here, job creation seems to have matched job losses, and statistically speaking, job positions have remained intact. What has decreased here is the number of unemployed people actively seeking jobs. We could say that there has been a churn of those looking for employment away from the labour market. For whatever reason, they have stopped looking, they may be making a living by renting out their real estate, working in the grey market or speculating in the capital market. In 2021, the job market is expected to continue its current trend of a larger number of employees moving around jobs, trying to adjust their livelihood.

Furthermore, the current administration’s success in keeping the job numbers stable despite the pandemic may well continue into next year. However, this could easily change if the next administration does not have the discipline or the will to follow on this path. It is possible that the coming government will prefer a superficial, populist approach in dealing with economic production and might choose subsidising people instead of businesses. That would ultimately create unrest among the general population for it can, as history attests, cause many ordinary people to fall through the cracks.

Unemployment rate decreased throughout 2020 in what seems both a smaller labour market and substitute means of income, Iran Statistics Center

Capital Markets,

the Panacea for Budget DeficitAs cash became tight in 2020, the government inflated the Tehran Stock Exchange, TSE, with the aggressive introduction of ETFs and by inviting first-time retail investments. Then came more bloating, combined with crisis management. In July, when the main index, TEPIX, had already passed the 2,000,000 mark, or a worrisome 300% above its 2020/Q1 start, the government allowed a massive and widespread revaluation of assets of companies listed on TSE to prevent a market crash.

By early August, the Judiciary and the Parliament objected to additional government ETFs and the exchange eventually started its inevitable nosedive. In reality, it had become especially complicated when the government decided to put major automotive players in its public ETF. That fund never materialised, and soon after, the cabinet lost its Industry Minister to an impeachment, arguably launched by major car manufacturers and upstream steel players. The Minister was one of the many people and initiatives lost to the intense negotiations between the heads of state.

Soon after, the raft of new interventions and regulations for TSE unfolded daily, including very restrictive rules for short positions, the ability to sell stocks you bought on the market, while investors instead witnessed the introduction of new option contracts. In September, the online platform of brokers crashed trying to handle the queues, where about 80% of the market activity was by retail investors. The new measures implemented by the government helped curb the downward rush of the market. By November, the market seemed relatively stable from outside, but between October and November TEPIX was in fact quite volatile.

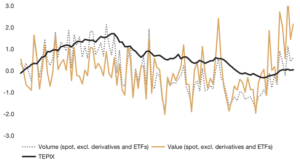

Tehran Stock Exchange’s volatile ride between late June and December 2020, with TEPIX moving near or above two standard deviations of its course since April. Based on data published by TSE.

Trade: Europe Stays, China Rises

By early 2020, the US had pushed to stop any trade flows in and out of Iran and put extreme force to wall in the entire economy, almost literally. New sanction designations came in every month and, by the time of the US elections, every week. The US also stopped extending exemptions for buyers of Iranian oil, most notably India, and made it hard to bring in the money for the few remaining exemptions, such as electricity exports to Iraq, an energy lifeline that is a matter of security for Iraqi and coalition forces inside Iraq.

Additionally, the US or the British confiscated Iranian tankers to the point that Iran sent its ships to the Mediterranean allegedly escorted by the Russian navy. Next, the main pipeline for Iranian gas exports to Turkey was sabotaged in an explosion, and the resulting shutdown is said to have cost Iran about two billion USD. Lately, the UAE, a major hub for Iranian trade has stopped issuing visas to Iranians as it started embracing a wave of Israeli businessmen. And Israel could be seen in an advance from Iran’s northern flank in Karabakh as well. The idea that Iran would turn into another North Korea was never picked up, as its geopolitical location makes such a scenario almost impossible, but Iran has been boxed in tightly and confrontations at its borders have been barely short of an outright war.

Iran’s Q2-Q4 trade flows in 2020 are distinctively lower compared to the previous year but are far from a disaster. In that 9-month period, Iran imported about 23 billion USD in goods and in return, exported 21 billion USD in goods and services. If this trend continues for the next four months, the figure would be about 18% shy of last year’s, give or take. The state stepped in to ensure each transaction of goods and cash is properly accounted for.

On numerous occasions, it revised its tier system of priorities which allow cash outflows for imports. It tried to navigate the complex streams of interconnected business groups and their claims for regulatory freedom and resources. It also continued to rein in the traditional money transfer businesses who use the trust-based Havala system. A short list of products was designated by the state as top priority and was allocated a preferential exchange rate as low as 13% of the open market rate. The list consists of all intermediate goods for various industries, mostly chemicals, agricultural inputs, metal scraps, pharmaceuticals, medical equipment components and some complex machinery parts.

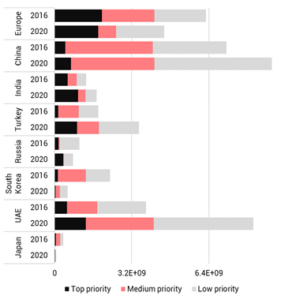

Ara research team thoroughly analysed trade flows in 2020 and 2016 and a review of the imports of priority goods between the two periods reveals Iran’s more reliable international Major currencies by value of imports in top-priority, intermediate goods, based on data from past two and a half years. Level of fragmentation is a composite index of the number of companies and their order sizes, indicating to what extent trade was concentrated within few players or dispersed among a larger number of importers; the lower the index the higher the concentration.

Imports of priority goods from select major partners of Iran,

2016/Q2-Q4 versus estimated 2020/Q2-Q4 in USD

trade partners. On the world stage, Europe is increasingly showing an opportunistic tendency for renegotiating the JCPOA which is exemplified in Germany’s comments at the United Nations Security Council in late June and its more explicit “nuclear plus” suggestion in December. Nevertheless, the level of Iran-Europe trade of high-priority goods stayed the same between the two periods.

The Europeans failed to unilaterally deliver their JCPOA commitments but did not follow the US withdrawal from the deal either. We do not see new models of European cars or consumer goods on the streets, nor are there any new direct investments in oil, gas and petrochemical industries of Iran. Most consumer goods or low-tech materials have not been imported because European companies stopped their sales, fearing secondary sanctions. And, either way, the Iranian government does not allow imports of almost any consumer goods or practically any other product which can reasonably be manufactured inside Iran.

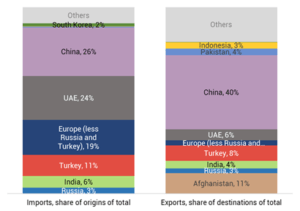

What came from Europe was then mostly parts that contributed to sustaining the current Iranian manufacturing ecosystem. China, on the other hand, along with Turkey, were the countries which were filling the gaps. For that reason, Iran tends to see its relationship with China even more favourably than before. Adding to this shifting climate is the fact that transactions through the UAE, which had less to do with the UAE’s political stance and more with its role as the regional hub, may soon decline as it is warming up to Israelis by pushing Iranians out.

While total trade has contracted by an estimated 18% in value from last year, Europe did not follow the US in the U-turn on the JCPOA and is still a significant source of high-tech or otherwise top- priority components to the agriculture, health and manufacturing. China, on the other hand, helped fill the gap in supply of key products and became the major market for Iranian goods, along with Iraq.

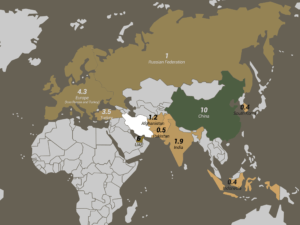

Iran’s major partners in 2020/Q2-Q4 by sum of imports and exports, in billion USD. Note: details of trade with Iraq are not publicly available, but the total is estimated at about 10 billion USD, almost entirely exports from Iran, making Iraq one of the major, or the single largest, market for Iran.

China, on the other hand, has kept the door to its market open so that close to half of all the money Iran is earning is coming from China. It should be noted at this point that the detail of about 10 billion dollars’ worth of mineral fuels, including crude oil, are not published by the Iranian government. Yet, it is safe to assume that the better part of it went to China. In practice, the People’s Republic has been arguably the most outspoken state to side with Iran in the international arena, along with Russia and Turkey.

To facilitate its eastward trade flows, Iran has been working diligently with its partners. Notably, there was the signalling news of upgrading Iran-China relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” At the same time, Iran has been involved in developing ports and facilities in the Gulf of Oman in coordination with

Pakistan, has inaugurated Afghanistan’s first commercial railway that connects with Iran, and has developed roll-on/roll-off ports to the north of Iran with streamlined and incentivised processes for trade on that route. Meanwhile Iran is looking to utilise a 32-offloading-terminal, $1.6 billion port in the Russian town of Lagan on the Russian Caspian coast which is allegedly being developed by Chinese contractors.

The Iranian government stopped publishing data about its exports of oil and gas this year, but market players took turns guessing at the number. Sending tanker fleets to Venezuela especially drew a lot of attention. Iran sent petroleum and petrochemicals to Venezuela and has allegedly recently started to even bring back Venezuelan oil to sell elsewhere.

By August 2020, Iran announced plans to intensify crude oil extraction in a project probably with the Chinese Sinopec and China National Petroleum Corporation. As it had lost a few tankers to US forces overseas, it also changed tactics. Satellite imageries from September seem to show Russian navy ships escorting an Iranian oil tanker in the Mediterranean.

At the same time, estimates of daily oil exports by Iran saw an increase, which seem to point to more than half a million barrels per day. It is telling that those developments came soon after IRGC‘s construction arm, which is developing fields abandoned by the Europeans, suggesting it would barter its fees from the government in barrels of oil. Additionally, the government has signaled it plans to sell an estimated 700,000 barrels a day next year.

There are no data as to who the buyers of the crude oil exports in Q2-Q4 were, but after Biden’s win in the US elections became clear, India also expressed its will to get back to buying Iranian oil.

India’s Take from the Iranian Crude Oil

India stopped oil imports from Iran in mid-2019 after the Trump administration did not renew its exemptions. By that time, India had imported about 2.8 to 3.5 billion USD from Iran. The country imports about 10% of all crude oil exports globally, at about 220 million tonnes a year. Iran was the top supplier to India, along with Saudi Arabia and Iraq before the 2012 sanctions.

Outlook

There are the complications in the transfer of money. Iran expressed commitment to coordinated anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing activities back in 2016. It established FATF-compliant cash declaration regimens and introduced draft amendments to its relevant laws in 2017.

However, as Trump started to push for confrontation, Iran put its imminent ratification of the Palermo and Terrorist Financing Conventions on hold. Since then, Iranians have used small fin-techs, traditional money businesses and are leaning towards yuan-based trade documents, while they contemplate the cost-benefits of returning to cooperation with that international body.However, designating the entirety of the Iranian banking system, including the meticulously sanctions compliant Middle East Bank of Iran, under the US Treasury’s counter-proliferation authority was one of the blows below the belt that Trump threw as late as October. The JCPOA signatories should show a clear gesture of good faith, and as a matter of simply giving economic weight to any talks within that framework, start off with re-establishing the SWIFT connection.

There is also the issue of sanctions and how fast and how thoroughly they can be reversed. Even though the US has sent nuclear bombers just outside Iranian airspace to make threats, the likelihood of an all-out war, is slim to nil. However, there is unanimous agreement among analysts that the US sanctions against Iran are not going to go away soon, and it is not a matter of politics. Even if Biden were to re-join the JCPOA on his inauguration day, it would take a painstakingly long and complicated process to re-negotiate each sanction and designation one by one. European businesses would be wary of hasty re-entry into the Iranian market before they see more stability and a lower overall country risk.

Still, in 2021 international trade activity of Iran should be poised to gradually return to normal and the country can get back on track to become a global trade player. The return of a healthy level of trade would mostly come from initiations by Iranian importers and exporters, rather than direct entries from other nations. Chinese investments in Iran during the Trump administration may not have been considerable, especially relative to their trade with the US, but they have been fundamental. China seems to have created a permanent footprint in Iran that is hard for any other country to replicate, at least in the short to mid-run. Iran is also developing its infrastructure to work with the Eurasian Union but its current potential value seems still relatively small compared to, say, Europe.

Iran’s location does not permit a closed economy, and its size and weight can only be contained for so long. Foreign aggression cannot change Iran’s state and people’s choices, and would not succeed in Iranian subjugation. Iran has shared borders with the West and the East for eons. It has only been the flow of goods, and with it the flow of people and thoughts that have shaped its mind-set and eventually its relationships. One thing is clear, though, Iran seems to have survived the Trump presidency, putting the harshest economic period of its modern history behin .

Iranian Industry Looks Positive

As an indication of what to expect, looking into 2021, Purchasing Managers’ Index or PMI’s healthy range and growth signals real GDP growth. Industrial and fiscal policies are proving to lift the economy, while Iranians are being innovative with workarounds for supply of inputs and international money transfers issues.2020 PMI adjusted, weighted average, own calculation

based on data published by Iran Chamber of Commerce.