By: Farid Atighehchi

In late April, at the end of an editorial in an Iranian newspaper, its author suggested that Iran should respond to Israeli sabotage of Natanz by attacking the nuclear site in Dimona, Israel. Less than a week later, a heavy missile was launched from Syria and landed a few kilometres off the very reactor, 200 kilometres into Israel. Iran allegedly threw a punch, meant to reciprocate. This came as the covert, unfriendly exchanges between the two countries were being dragged into an open arena. But these days both adversaries seem to keep the feud contained, and the risk of war has apparently ebbed before becoming real.

While Military contestations were being curbed, the overall economic activity, investment performance and consumption were brutally tested by the pandemic and US sanctions, and yet overall, the Iranian economy showed resilience once again. There is no mistake the toll of the sanctions and the pandemic have been heavy and have made life and business complicated but companies, including those in the so-called informal economy, are hiring. Salary levels are rising –be it at a lower pace compared to prices. And despite sanction-induced shortages in some intermediary goods, almost everything is available in the market. Certainly part of that supply comes from stockpiles and inventories from before the sanctions but the risk of their complete depletion before finding substitutes or new sources seems low.

The crude oil production is projected to rise to 2.8 to 3.5 million barrels per day before October 2021, according to the Eurasia Group. And unofficial estimates of Iran’s February 2021 oil exports are between 700,000 and a million barrels per day.

Here we review the key developments to watch and their culmination in the coming months. And we will examine how, against that background, different sectors within the Iranian industry are expected to operate.

What to Look Out For

The Lifting of Sanctions

The most significant development with an immediate impact is the lifting of the sanctions. Earlier expectations of an interim deal in May suggested that the process would take until about October 2021. The removal of the sanctions would help the recovery of Iranian Rial as well as being a boost to government investment, net exports and consumption. Still, a big chunk of the economy, i.e. the parastatal entities, have previously been shown in studies to bounce back more slowly and as such they will slow down the overall GDP growth.

The Vaccinations

Between February and late June 2021, Iran vaccinated more than 5.3 million people in the priority groups with at least their first dose, only a little over 10% of whom having had both doses. The government has pledged to vaccinate all adults above the age of 18 by March 2022. That requires administering about 12 million doses a month, which basically means the logistics, let alone supply, should outperform that of the current US efficiency by 40%. Either way, the impact of the pandemic is going to weigh on business activities and consumption for another year before it gets a chance to return to its pre-Covid levels.

Rises in Consumer Prices

The government enacted interventions Included the choreographed rise in prices of food, public transportation, and housing, carefully Sequencing each increase in prices. It also did not whittle down energy subsidies for the time being, despite the clear mandates that have been in the works which will kick in again sooner or later.

Higher Employment

At the same time, the rise in job offerings will support income although calculations using data published by the government suggest that about 900,000 people had already lost their jobs by the second quarter of 2020 mainly due to the pandemic. Therefore, new jobs may only get to compensate for losses incurred so far, not create net new employment.

There has been accompanying increases in salary levels with what may be, only partially, a push by the labor market, independent of and beyond the State’s interventions. This might be high enough to raise disposable income in different populations. Future studies may reveal if this boost has helped alleviate an increasing wealth gap or is limited only to some income groups. Nonetheless, these developments seem to support the current level of consumption, inevitably still lower from before the 2018 sanctions. While the aggregate levels should hold steady, their growth, or decline, may be easier to see among different product categories and among different income groups.

The Presidential Elections

The campaigns for the presidential elections gave few coherent clues as to what the agenda and approaches of the next president is going to be. Arguments about the fundamental arrangement of power are also gaining momentum, in a clearer expectation they are inevitable. For the time being, the Parliament is fiddling with the structuring of the executive branch. However, such changes, and the leanings of the next president will not come into play for many months. The reality is that the result of the elections is of much less significance than the economic impacts of the public health issues and foreign policy, and businesses seem to discount the presidency in their calculations to some degree. That being said, we can expect a healthy economic boom for the next couple of years as President-elect Raisi is expected to increase government spending and the potential revival of the JCPOA can only accelerate any such economic growth.

Quotation: “We can expect a healthy economic boom for the next couple of years as President-elect Raisi is expected to increase government spending and the potential revival of the JCPOA can only accelerate any such economic growth.”

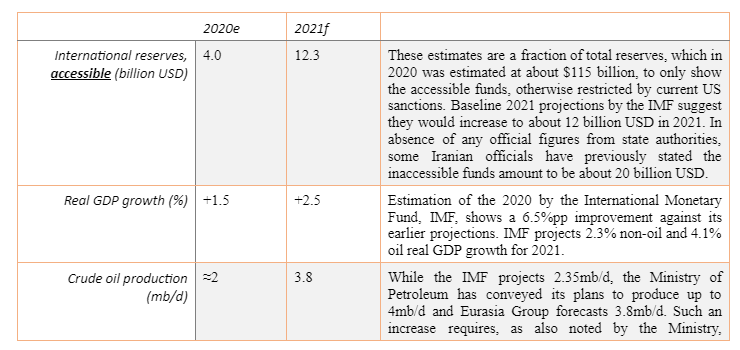

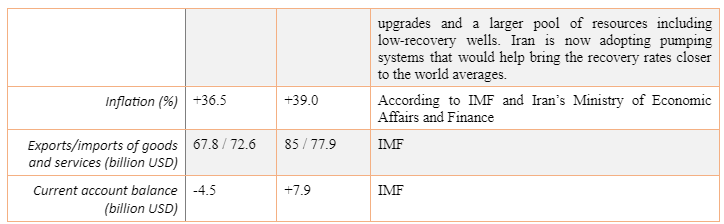

↑ Figure 1 Key indices of Iranian economy in 2020 and 2021

↑ Figure 1 Key indices of Iranian economy in 2020 and 2021

These estimates are a fraction of total reserves, which in 2020 was estimated at about $115 billion, to only show the accessible funds, otherwise restricted by current US sanctions. Baseline 2021 projections by IMF suggest they would increase to about 12 billion USD in 2021. In absence of any official figures from state authorities, some Iranian officials have previously stated the inaccessible funds amount to be about 20 billion USD.

Real GDP growth (%)

Firms of Endearment:

Regulator-Industry Tensions

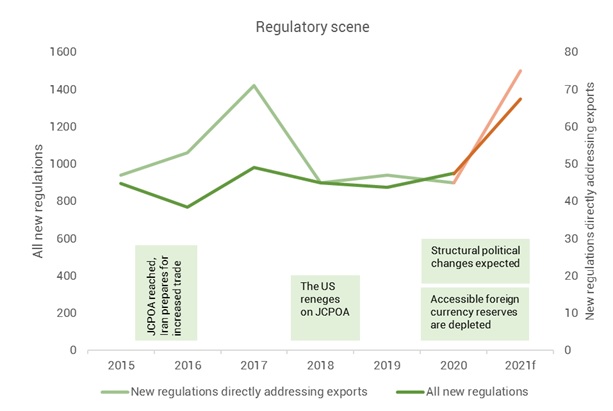

Reviewing the regulatory scene gives us an idea, even if partial, of the changing business environment in Iran. After the JCPOA was signed in 2015, the total number of new regulations, from all regulation-setting state bodies, dipped down, except for those directly pertaining to exports, which took a steep rise in preparation for the negotiated, unblocked trade channels. But the US breach of their commitments and their besieging of Iran with extra pressure cut the country’s access to parts of its foreign exchange reserves. The impact was evident in a heated dispute between Iran and South Korea that saw the visits by Korean delegations, including for the first time since the revolution in 1979, the visit by the Korean Prime Minister.

“Dispute over Iran’s frozen funds in South Korea resulted in thefirst-ever visit by a South Korean Prime Minister after 1979.”

Between 2016 and 2018, the nuclear deal did not deliver any tangible benefits; and then came the U-turn in the US foreign policy towards Iran which prompted a wave of currency devaluation, inflation and recession. Consequently, by the end of 2020 the government and the Central Bank of Iran were already introducing regulations one after another to control the flow of goods and money. This was most apparent in the control of imports and in the excessive interventions in the Tehran Stock Exchange.

In the first quarter of 2021 there were more than 400 new regulations, 25 of which directly related to exports. In part, this was because of an expected structural change in the fundamental political arrangements in place.

“High regulatory complexity since 2018 comes out of necessities to manage crises but it is also currently the most complicating factor for businesses.”

These dramatic changes in the regulatory scene are indicative of the uncertainties the State and, in turn, the businesses face in their operations. The nuclear talks are still going on in Vienna in hopes to revive the JCPOA. However, reaching an agreement and then its implementation are both time-consuming and present many uncertainties. In the meantime, the combination of regulation complexity and rising taxes have evidently pushed some activities deeper into an informal economy. Notwithstanding, the state also seems to have learned from previous experiences, especially those between 2006 and 2016, and has made successes in, for example, stopping subsidized foreign currency to end up in the imports of non-essential goods.

↑Figure 2 Number of new regulations from all State and legislative bodies until the first quarter of 2021,

also showing the current trajectory into later this year.

There is also the new administration which is expected to reinforce this regulatory complexity. But at the moment, that is not as much of a concern for the market as are the sanctions and vaccinations.

Overall, the ongoing pandemic and its impact on purchasing behavior and supply chains, infused with the global isolation of the banking system have caused a sustained level of stress in securing manufacturing input. Access to these inputs and their additional costs remain a constant on the top grievances of manufacturers, as reflected in surveys by Iran Chamber of Commerce.

Emerging Perceptions and Realities

Sample Posted Job Vacancies

There are some faint signs of favorable developments nonetheless. Many new policies and arrangements evolved to secure current levels of trade and business. By early 2021, this transcendence was reflected in the 25-year deal with China –rather symbolically as it does not seem to be a sudden boost but a commitment to building on the current trajectory. Iran could potentially have more committed partners. The deal with the Chinese may well be a start to what could be a series of broader pacts with Russia, neighboring countries and other cohorts –with more obscure examples such as the recent signing of a military agreement with Tajikistan suggesting the direction of these developments. Because of the significance of the dollar in the global economy, Iran still needs to get to a détente with the United States, but the impact of the sanctions has gone from crippling to manageable and their power as a threat is waning.

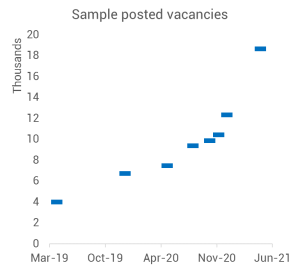

It is these adaptive behaviors, in addition to an optimism for a projected revival of the JCPOA, which is now contributing to a sudden recirculation of capital. Cash-flow problems are still prevalent in some sub-sectors more than others, but there is an increase in business activity. It could be traced, to some extent, by the increase of employment opportunities.

When firms expect a persistent rise in business activity, the number of posted vacancies usually rise. Although there has been a lot of employee turnover during the last year and some companies are merely refilling previous posts or restructuring their market positions, it nevertheless indicates a rise in activity. Taking a look at the number of jobs posted on “Jobinja”, one of Iran’s leading job listing platforms and popular with private companies, in April of this year, and while still months away from a public vaccination rollout, we can see that the number of listed jobs has jumped close to 20,000 –a five-fold increase compared to the first shock from the pandemic.

←“The number of posted vacancies rise when firms expect a persistent improvement in business activity. In our sample, job postings have multiplied especially since November 2020.”

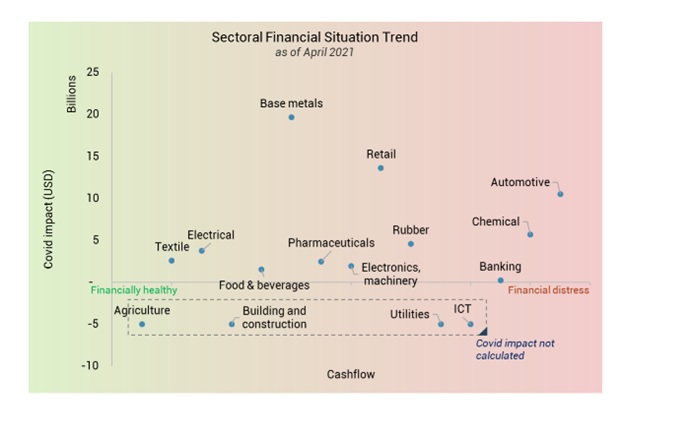

But this expectation of growth is not evident in all sectors. Investigating the performance of public companies shows which ones are closer to financial distress. Automotive, chemicals, banking and ICT (Information and Communications Technology) are either more afflicted or are more susceptible to cash-flow problems. The reasons are different. For example, the banking sector did not suffer much from the pandemic, but it is not exactly in good shape after a sharp decrease in the economic activity, exacerbated by the rerouting of cash-flows from the formal system to the underground. The ICT sector’s problems seem to be mostly unrelated. Despite the uncomfortable situation with the supply of key equipment, the sub-sector of telecommunications seems to be mostly grappling with decreasing revenue-per-bit, fueled by its own trend of technological and business model disruptions.

Base metals and retail find themselves in a different situation. Base metals are suppliers of intermediate goods to many sectors including the automotive industry and their upstream position helps them steer away from cash-flow problems but only as much as the pandemic indulges demand. At the other end of the value chains, retailers are also limited by demand while their supply has been available or substitutable.

↑Figure 4 Above graph is based on a preliminary modelling effort and presented as indicative.

Covid-19 impact is based on estimated lost revenues as a result of disruptions in production, supply chain or sales. Cash flow estimate is based on stock price trends in Tehran Stock Exchange between November 2020 and April 2021.

Expected Reactions and Opportunities

Against this backdrop, the response of these sectors will vary. Those in better shape will attract more investment for earning growth and have the luxury to focus on competition, while others, whose revenue growth plans are stymied by cash-flow problems in their industries, will behave differently and try to just survive the current economic trends.

Different sectors are in different situations. Their responses will show in the mergers and acquisitions and in changes of board members.”

Responses will be visible in the number of mergers and acquisitions and in changes of board members. This wave of mergers and acquisitions gradually picked up during the past two years, but the next few months will be critical for companies to forge new alliances and to build up resilience or recover.

We expect companies more prone to capital problems, e.g. automotive, banking, chemicals, ICT and rubber, to exchange ownership stakes with other companies in their value chains who could help them improve their operations, find financing, secure inputs or offer access to other markets.

Firms with healthier financial prospects, e.g. agriculture, textile, electronics, food and beverage, construction and pharmaceuticals, would bring new faces with governmental backgrounds to their boards, but would also regroup in holding companies, where a central actor takes the responsibility to interface with the State.

Firms with less severe cash-flow problems, would look for merger and acquisition opportunities to help their operational processes and may be hopeful for multiples in their post-money valuations.

This understanding of sectoral differences could help highlight and develop opportunities. International players could fill the gaps as long as they appreciate the predicaments of each sector: Expectations, common in a normal, thriving environment may need to be replaced by relevant concessions or assets. For example, in many sectors the regulatory complexity holds the prospect of extra operational costs, so lowering transaction costs and prices could secure international companies better deals with Iranian prospects.

“Understanding peculiar situations that firms in each sector are in, helps highlight exact opportunities and guide negotiations between Iranian and international players.”

In the market, each sector would take different strategies as well. Automotive, chemicals, banking, ICT and utilities would focus on cost reduction. Pharmaceutical companies and the few automotive players would focus on influencing regulation and market dynamics in coordination with other players in their respective markets. Some of them may even find the opportunity to break into new niches as well. For example, Bahman Group, which is a large car assembler in Iran, has long been striving to place itself among the market leaders, along with Saipa and Iran Khodro, but its sales is dwarfed by the two. As established car players may be vulnerable now, private players like Bahman may be able to position themselves more favorably against the oligopoly. An impeached Industry Minister and two acting ministers later, Bahman only recently announced its Euro-6 engine production is operational and, according to the deal signed last year, it will sell the engines in numbers many times its own production of vehicles.

Companies in textile, agriculture, building and construction, base metals and rubber, on the other hand, would attract and allocate more experimental investments to develop options for the future. Some companies within these sectors may, sooner than later, even opt for a focused approach and compete comfortably on costs or differentiation.

Crucial Decisions

Different sectors, and different sub-sectors within them, must develop a manifold of ways to survive, innovate and grow. Their success relies on many factors but to a large extent on the openness of the economy. Speaking with businessmen, many assert a positive outlook where, while direct foreign investments may remain scarce, it would take no time for Iranian businesses to reinvigorate cross-border trade. And while trade with the West is conditional to the outcome of the Vienna talks, routes to Eastern markets are already being established and reinforced. The level of uncertainty has decreased, and mid-term planning is much more feasible now. And perhaps most importantly, the market seems to assign a score of “manageable” to perceived risks in comparison to foreseeable rewards.

“Speaking with businesses, many assert a positive outlook. Some, inspired by the resilience of the economy and the successes of recent localization efforts, also hope their industries stick with strategic local productions.”

Many are also hopeful that the involuntary commitment to value added domestic manufacturing sticks. That would see further emphasis on technology and capability upgrades, refusing a historical tendency to favor imports of finished goods.

Right now, politics, regulations, trade and market players and their uncertainties are in the open, and the status quo has already been challenged –both exogenously and by the State itself. Next few months, and how regulators, investors, politicians and businesses pick their next moves, could not only seal their individual outcomes but may also have a lasting effect on Iran’s place and prowess in the global value-chains –and on the wealth and welfare of its people.